The Hunger Virus

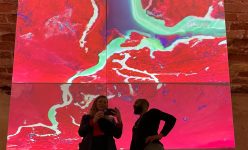

All markets in Rivers State have been closed. Many traders find it difficult to accept the shutdown.

According to Mrs Williams, who was at Creek Road Market the morning after the state governor declared the closure, people at the market are still going about their businesses. With the pervasive threat of both the virus and state security forces patrolling the area, market sellers are risking their safety in more ways than one. Many feel they have no choice.

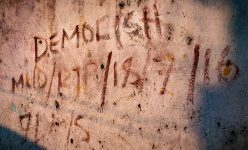

“Making secret sales in the market has given me my daily bread,” said one of the traders, “and it has also helped me to feed the family properly, since there was no stay-at-home allowance or relief package from the government.”

Other traders we spoke to also said that they violated the governor’s directive because they needed to make ends meet.

“We go to the market by 4am in the morning and leave immediately by 6am when the security agencies would arrive their duty posts and before the task force would also arrive the market,” said a market woman.

Mr Joseph, the owner of a kiosk store, said that if he didn’t go to the market each day to fill up his shop, the people in the community wouldn’t be sustained by their ‘petty petty buyings’, since not everybody has the money to stock up.

A man, voicing a common concern expressed in the community, said, “We need the restaurants open and the kiosk stores available to help us in this period of time.”

“An additional 20 million people could struggle to feed themselves due to the socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 in the next 6 months”, Elisabeth Byrs, Senior Spokesperson for the World Food Programme, claimed on 5 May.

“What we see now is ‘hunger-20 virus’ — in other words, due to the lockdown and the cost of things, life would be very hard,” said a local buyer. “Without the market, we don’t think we can survive in this period.”

Increased food insecurity and the inadequacy of government’s ‘palliative’ measures point to the urgent need to rethink public health policies around food markets in Nigeria. Markets are a vital part of cultural, social and economic life in a city like Port Harcourt — goods, food, gossip, ideas and money circulate rapidly. So do germs.

The response of the Rivers State government has been either to close them or to restrict market opening times. But this approach has been counterproductive as a public health measure, either driving people to dense ‘secret markets’ or forcing them to crowd between stalls during the few hours they are open.

If, instead, they had encouraged markets to stay open 24 hours and better regulated them, customers could space out through the day and night, improving access to food and essential goods, while allowing greater distancing. Such an approach might also signal a government more in touch with the challenges faced by many trying to navigate a public health emergency while living hand-to-mouth. Without popular support, many emergency measures are likely to fail.

“The Rivers State government should have pity on the poor people,” said an angry trader, “because not everybody can afford a plate of food for the day. It’s from the market we are sustained.”