Never Too Old

My friend George greeted me with a weak smile, trying to hide concern. “My dad slept in this police station last night,” he explained. He pointed to the Area Command of the Nigeria Police Force, Barrack Road, the building opposite Banham Memorial School.

“For what?” I asked, surprised. George’s dad, George Isaac Senior, was quite an elderly man.

“For mistakenly knocking down two six-inch blocks from the new ongoing traffic stand,” he replied.

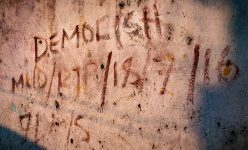

I remembered that there was indeed a traffic stand at the centre of Agip Junction, supposedly constructed by the police station’s DPO. Now, vehicles drive over a sandy heap on the ground.

I turned to look at the now-demolished structure and thought, “What happened to the rest of the blocks?”

As though reading my mind, George explained, “Other drivers ran into them, but only my dad will be paying for everything.”

On the evening of 7 October, George’s father, a 68-year-old commercial driver, left home for the first time in a month. He didn’t feel well, and had been trying to stay home as much as possible to avoid catching COVID-19 and getting even sicker. But his family was running low on funds and he had to do something.

When he hit the traffic stand, he got out of his car immediately to inspect the damage. A traffic warden who had seen the accident rushed over. Ignoring George Isaac Senior’s offers to fix the two blocks he had damaged, she pushed past him, jumped into his car, and insisted they drive to the nearby police station. When George Isaac Senior continued to plead with her, explaining that he was not feeling well and thought he may have malaria, she called her colleagues over. George Isaac Senior drove to the police station with his new traffic warden entourage in tow.

When George Junior arrived, an hour after the accident had happened, his father was sitting silently behind the police counter, his head in his hands. George appealed to the police officers, asking them to release his sick father so that they could simply replace the two cement blocks that had been damaged. But they were told that they would have to wait for the station’s DPO, Mr Daramola.

One police officer, sensing the unfairness of the situation, offered to sign a ‘surety’ with a pastor as witness, promising that the George’s would return the next day to fix the stand. But the police officer, too, was ignored.

The DPO never arrived. At 11pm, George Isaac Senior, now feverish, was stripped to his boxers and thrown into a cold, damp cell. As he lay on the floor, soaked with the stains and smells of previous prisoners, he wondered how he could have his car, clothes and rights stripped in a split-second, over two cracked bricks.

Section 34 of Nigeria’s Constitution in theory ensures his protection from “torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.” It offered no such protection now. Nor did Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights ensuring “respect of the dignity inherent in a human being”; nor Sections 98 and 99 of the Criminal Code, or section 115 of the Penal Code, barring all forms of police extortion. Under these codes, public officers demanding bribes are guilty of “official corruption” and are liable to seven years’ imprisonment — but it was George Senior who was shivering himself to sleep in a cell that night.

His son returned to the police station the next afternoon, after spending the day trying to scrape together cash for his father’s bail, and then wearing down police officers with renewed promises to replace the blocks.

Police Bail in Nigeria is free, yet officers illegally demand cash for bail. This is standard practice. Just as he had posted his father’s N10,000 bail, the DPO arrived. Daramola insisted that, instead of the family replacing the blocks, he should be paid N50,000 directly, calling the stand his “personal project.”

George refused. Fortunately, they were able to return home anyway. They left the police station to find that the traffic stand had been completely destroyed overnight by other drivers.

On Saturday, father and son returned, not only to rebuild the traffic stand but to improve it, raising the platform knee-high, upon the insistence of the station’s police officers. And, as a reward for his forced labour, George’s father’s car was released back to him.

As young women and men across Nigeria protest police brutality, security forces show they don’t discriminate on the basis of age: the old can also have their rights violated; the police demonstrate they can be equal opportunity extortionists.

‘George’ and his father asked for their names to be changed for fear of reprisals.