Shutdown Start-Ups

With Schools Closing, Students Are Opening Businesses

“It’s sort of a blessing in disguise,” says Dienma Alphios about his university being shut down by the government due to coronavirus concerns.

“It has affected my educational career […] But for my private life, I am chasing lucrative activities and building up skills. I use this opportunity to do some other stuff.”

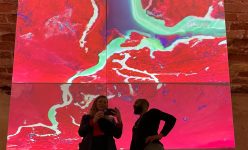

Dienma’s daily commute now takes him no further than his doorstep. Instead of writing papers at university, he trims beards and shaves hair in the narrow alleyways that run through his waterfront community.

Armed with a pair of clippers plugged into his living room socket and an old toothbrush to tease beard hairs into shape, he serves neighbours and friends who all need to stay fresh regardless of government directives that sometimes put restrictions on non-essential businesses.

“I cut hair,” he states, proudly. “That’s my handcraft skill. I’m a barber. So I’m trying to work on that.”

Although Dienma is studying religious and cultural studies at university, he doesn’t see his humanities degree as an immersive learning experience, nor as a way to explore, experiment, and evolve.

“Going back to school is a priority because we really need to get the certificate,” he explains matter-of-factly, wrapping an ankara cloth around his customer’s shoulders and fixing it at the neck with a faded clothes peg.

“But then at least you can say you are going back to school with an added skill, not just ‘bookwork’.”

Dienma is also using the time off school to cultivate other practical skills. As well as etching funky designs onto people’s scalps, he is developing his long-held passion for digital design, experimenting with Photoshop, Explore and Blender.

Franklyn Chukwunonye is a student of Human Kinetics at Ignatius Ajuru University of Education. He’s also a poet. He often finds himself frustrated with his schooling, which he says encourages him simply to regurgitate information from memory in order to pass exams, while failing to foster his creativity and imagination.

“Honestly, education is one the greatest things a man should acquire because an educated man wouldn’t be ignorant, I believe,” he says. “But our system is focused on their selfish interest and the certificate only, and not education.”

He further explained, “There are a lot people who don’t know they’re trapped. To them, they’re acquiring skills and knowledge. But they’re just chasing papers.”

Belema Gibson, is a third-year student of adult and community education at Rivers State University of Science and Technology. Despite the focus of her study, she is not invested in the deeper value of a university education that Franklyn holds to. Nor is she focused on chasing certificates. She has had so much success with her new online business that she doesn’t foresee returning to university.

“I don’t read anymore,” she says. “I don’t even concentrate. I don’t even think of school. I don’t want school to resume anymore because I’m now comfortable the way I am. I am earning money so I don’t want school to resume. It has made me forget the fact that I am a student.”

“It’s quite unfortunate that this type of attitude is very prevalent and common,” comments Professor Ebiegberi Joe Alagoa, Professor Emeritus of History at UNIPORT and one of the most distinguished academics of the Niger Delta. “That you just want a certificate, that is more important to them than acquiring knowledge that they will use to better their lives. Education is to develop the mental, social and cultural quality of the person.”

Professor Alagoa explains that because the economy is in recession as universities are producing more and more graduates, the competition for formal jobs is so fierce that students focus too much on graduating as quickly as they can so that they can get out into the world and start hustling. But there is often considerable skill and ingenuity in the hustle.

Belema runs an online fashion retail business, ordering bags and clothes directly from manufacturers in China, which she then resells via her social media platforms.

“I will contact the producers and pay the shipping fee,” she explains. “Everything is just online. With the help of my phone I will pay for the goods, the goods will get to me and I will give them to the owners.”

As this is her first business venture, she was initially nervous. She remembers worrying about whether or not to bulk-buy goods.

“Will they buy? What do they want?” she remembers asking herself.

At a time when a pandemic is disrupting supply chains, Belema is negotiating international relationships with vendors, dealing with global logistics and leveraging social media platforms in innovative ways to get her product out.

The suspension of studies has posed a more pressing issue, though, for those who already struggled to pay school fees. The pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns brought about unexpected costs, and many are now concerned they won’t recover financially in time for the resumption of school.

“This July, all things being equal, if there wasn’t this lockdown, I should have been defending my project,” says Dienma. “But since the pandemic and the lockdown and there is no other means for continuation of studies, it’s just going to extend my academic session.”

Erak Rouna, a final year mechanical engineering student is disappointed that universities didn’t deliver on their initial promise of continuing education through digital platforms.

“They actually said they were going to do that [online learning] but later they didn’t,” he says. “I think it was not possible. They were having issues with the online app configuration.”

“It was promised but it wasn’t fulfilled,” agrees Belema.

Besides e-learning, there were no assignments given to these students to complete at home over the period, nor any other educational requirements.

“When school is shut down like this, we need to look for other activities to keep us busy,” says Erak. “We need to learn skills.”

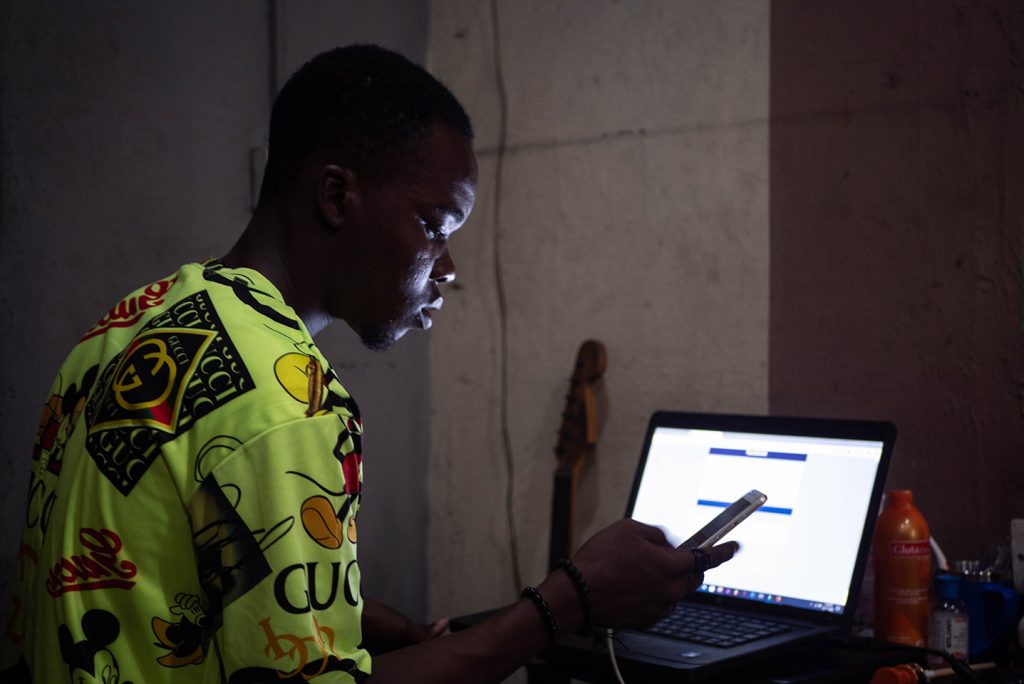

But he is confined by the lockdowns. So he has turned his attention towards online courses and trading, which he can do from the comfort of his bedroom. He sits at his small glass desk, which is cluttered with medicine, toiletries and now gadgets — one laptop resting on top of another, his phone plugged in and a keyboard balancing on his knees.

“I learned a lot of skills online, like graphic design [and] FOREX,” he explains, his face lit by the blue glare of his laptop screen. “I have developed myself to an extent at which the skill I learned is really paying financially.”

This educational hiatus cannot be blamed solely on these viral times. The Nigerian educational system has long been marked by academic staff strikes that have sometimes gone on for years. In fact, even if it weren’t for the government’s coronavirus measures, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) has been on strike since March.

“Strikes affect the students very badly,” says Professor Alagoa. “Those that are doing research to write their dissertation, when the teachers are thrown out of the university, they are running around trying to find something to get a livelihood instead.”

But he states that the blame for the disruption lies with the government, and not with the academic unions. The government, overly involved in the monitoring and regulating of universities, tries to take control of the payment, exams and admissions systems, leading to conflict with professors who want to have the independence to run their universities their way, for the benefit of their students.

“Most of the time the academic unions are interested in gaining the autonomy of the university and setting up proper structures for teaching and learning,” he explains. “Even the students would have a bigger voice within their campuses about quality of education and the devotion of lecturers to the provision of knowledge. Professors would be able to work with students directly and relate with them. Right now, they are spending most of their time arguing with the government.”

On 2 October, the federal government finally announced the re-opening of universities, imposing new coronavirus guidelines such as mandatory hand-washing facilities and sick bays. Although most state and private universities are now open again, there are no lectures at many federal and public universities due to the ongoing ASUU strike. There has been strike action in seven out of the past 13 years. With decreasing resources being allocated to the nation’s tertiary learning institutions, the situation is unlikely to improve anytime soon.

The impact of education on a country’s development has been studied in depth. UNESCO recommends that ‘lower middle income countries’ allocate between 15% and 20% of their national budgets to education. For the past ten years, the highest percentage of the national budget allocated to education in Nigeria was 12.28%, in 2015. On Thursday, 8 October, President Muhammadu Buhari announced the national spending plan for 2021. Despite the fallout from this year’s disruption to education from both strikes and virus, that number will plunge to 5.6%.