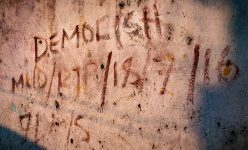

Never Expect Power Always

A favourite Nigerian pastime is complaining about our lack of electricity. In fact, we jokingly (or maybe not so jokingly) refer to NEPA, the National Electric Power Authority, the post-civil war consolidated public utility, as ‘Never Expect Power Always’. Later when the name was changed to the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN), we coined the new utility as ‘Problem Has Changed Name’.

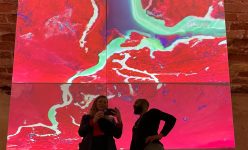

All the issues with major power outages and unreliable service, eventually led the government to enact the Electric Power Sector Reform Act of 2005. As part of this reform the electrical utility was unbundled and privatized. The national utility was separated into six generation companies, 11 distribution companies, and a national power transmission company. Our electricity bills started coming from the Port Harcourt Electricity Distribution Company (PHED), which serves most of the Southeast of Nigeria including Rivers, Bayelsa, Cross River and Akwa Ibom States.

Did this new privatised utility provide any improvements? Not that we can tell. Instead, you might hear us in Port Harcourt refer to PHED as ‘Port Harcourt Electricity in Darkness’. Even though the name has changed times several times, we often still lament about the utility using its old name ‘NEPA’.

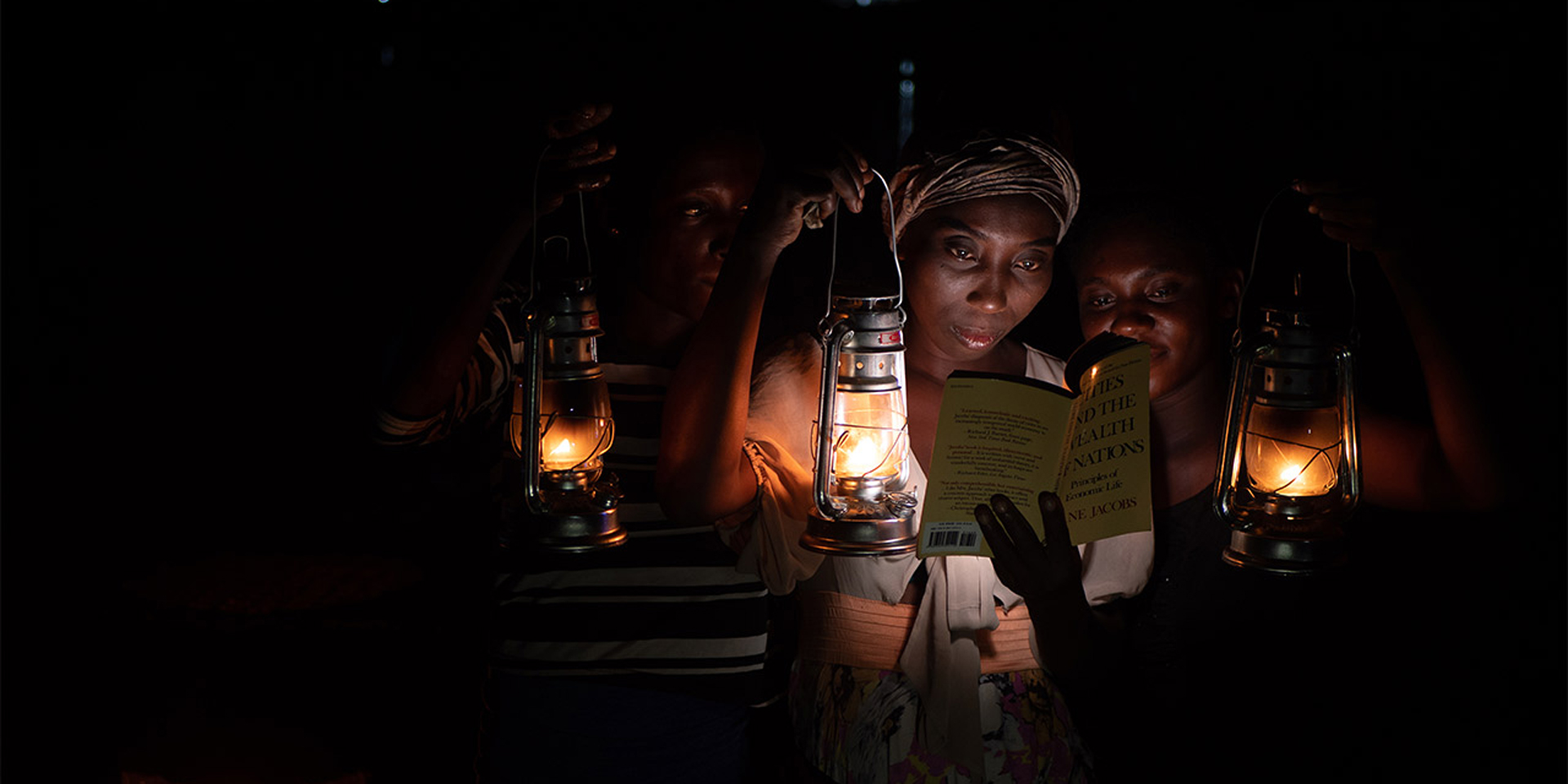

Power outages are so irregular and routine, that we celebrate on the streets when we hear the local siren go off marking the return of electricity and run home to plug in anything that can be charged. We know our electricity service is poor, but most of us don’t track how bad it really is. Inspired by one of our oldest mappers, Asifieka, who mentioned that he keeps a daily log of when electricity comes and goes to verify against his monthly electricity bill – we thought what if we did that at a much larger scale? How can we use our skills as mappers to collect and analyse information on electricity? What patterns would we find?

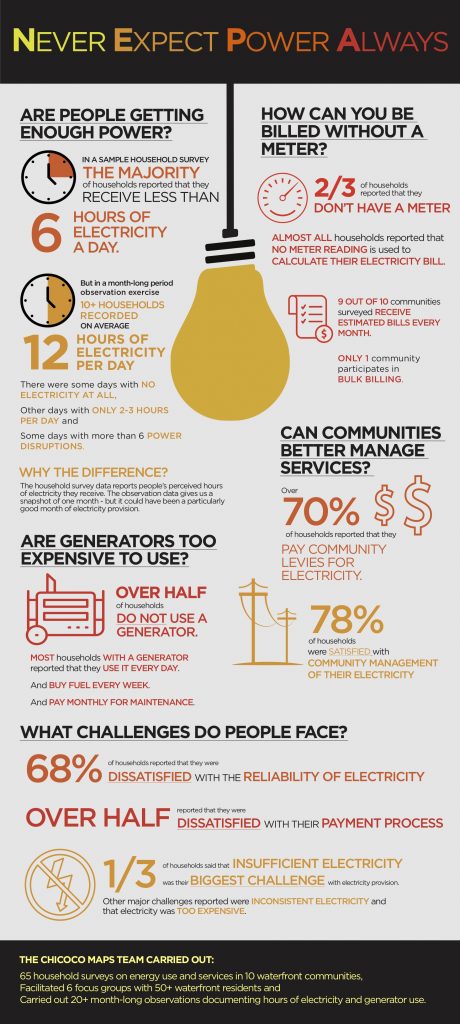

In July and August 2021, we scaled up Asifieka’s research to carry out 20+ household and business month-long observation exercises documenting hours of electricity and generator use. We carried out 65 household surveys on energy use and services in 10 waterfront communities and facilitated 6 focus groups with 50+ waterfront residents.

The results were not unsurprising, but we now have data to back up our complaints. And maybe we can think about how we can use our data to fill in the decade’s long gaps in poor service provision. Check out some of our findings in the infographic – aptly named ‘Never Expect Power Always’.

As we expected, most participants complained about their billing, particularly issues with estimated billing. Almost everyone has a have meter, but PHED staff do not read the meters. They just give them a bill based on how their household looks from the outside and not based on energy usage. People reported that they stopped reading meters when NEPA transitioned to PHED, way back in 2005. But the problem is that they feel stuck – if they don’t pay their bill, then PHED will cut off their power. So, everyone pays their bill, even if they know the bill is not based on any actual usage data. Many people said that they pay for eight hours of light a day, but that they do not often get that.

Our respondents stated that the communities themselves are more responsive and better at fixing faults. If they wait for PHED to fix a broken pole or transformer, it will never happen. The few times a community has tried to get PHED to fix faults they want to charge them huge amounts or it takes a very long time.

Across the board people said they would prefer an alternative energy supply, like solar, if it was cheaper than NEPA and provided consistent electricity. Many said they already pay for maintenance to the community and would be glad to pay if they had consistent light. And many households and businesses rely on expensive generators to fill the gaps. It’s clear that there is ample room for renewable energy options to supplement or even replace the grid. Will communities be better at managing and providing electricity? Well, we like to think they can’t be worse. After all they are already acting as utility providers. If the community is already raising funds through levies and actively constructing, managing, and repairing their own electrical infrastructure – why couldn’t they manage their own solar minigrid?