Blood for Blood

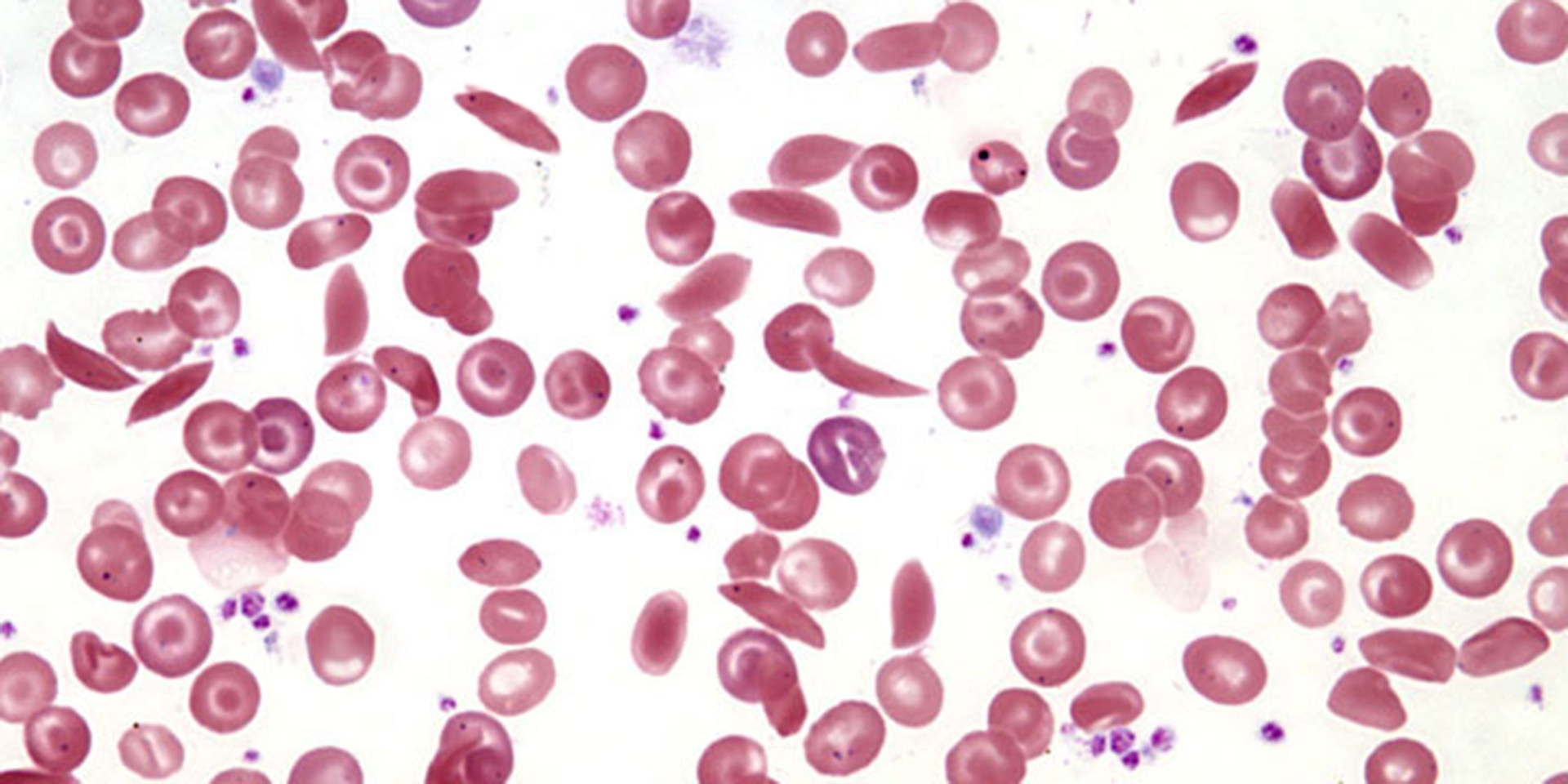

At 73 years old, Elder Asifieka Dede sits with his hands hugging himself in quiet reflection, his grief still fresh. His first son Tamuno-miebaka Dede, who would have turned 32 on 8th December, died just six months ago. It was a loss that shook his family and friends – a tragic ending to a lifelong battle with sickle cell disease and a stark reminder of the consequences of a failing healthcare system he relied on.

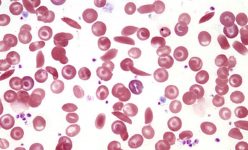

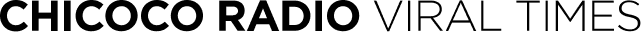

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is caused by abnormalities in hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying component of red blood cells. This genetic disorder transforms healthy, circular red blood cells into a sickle shape, leading to premature cell death, reduced oxygen flow, and recurring episodes of intense pain, known as “sickle cell crises.” Without immediate blood transfusions and medical attention, these crises can be fatal.

About 50 million people worldwide live with Sickle Cell Disease, and about 300,000 newly diagnosed Sickle Cell Disease children are born worldwide annually. Nigeria accounts for 100,000-150,000 of these newborns, contributing 33% of the global burden of SCD.

Elder Dede recounts how he and his wife married without undergoing sickle cell trait testing, popularly known as genotype testing in Nigeria. This decision would haunt his family. “I was not aware of my blood group before we were married, na jolly jolly na,” he says, shaking his head.

When Tamuno-Miebaka was just one year old, he began falling ill frequently, often requiring blood transfusions. The young parents were confused and helpless. “Me-self confuse, I don’t know,” Elder Dede explains kissing his lips.

It wasn’t until Tamuno-Miebaka turned five that a blood test revealed the truth: he had the SS genotype, meaning, he inherited the sickle cell gene from both parents. In Nigeria, an estimated 25% adults have the sickle cell trait (SCT). This is a genetic condition where a person inherits one sickle cell gene and one normal gene from their parents. People with SCT are usually healthy and don’t show symptoms of sickle cell disease (SCD). However, they can pass the trait on to their children.

Another Sickle cell warrior who wants to be identified only as Chioma, 18, told us, “I spend most of my time in the hospital bed because the hospital bed is like my second home.” Uncertain about her future, Chioma lives with her younger sister and petty trader mum who sells pumpkin leaves in the market. “No one with sickle cell lives past 20,” Chioma claims. Those with SCD do tend to live shortened lives. However, with proper treatment, those with SCD can live well beyond 20. Such treatment, however, requires resources: either a functioning public health service or the means to cover the costs of private care. Blood is not cheap.

Living with sickle cell disease in Nigeria is a constant battle, not only the pain and debilitation but also the struggle for money to pay for care and treatment. Blood transfusions are a lifeline for sickle cell patients.

As well as the physical pain and financial burden, sickle cell warriors and their families often have to endure stigma. “Some of my classmates and teachers in school think that I am possessed by a demon when I have crises,” Chioma explains to us, reminiscing on her experiences.

The struggle for families to help keep loved ones affected by sickle cell disease alive highlights the urgent need for better awareness and support systems. Sickle Cell Awareness and Health Foundation (SCAHF) was founded in June 2018 by Dabota Omobo Pepple, an accident and emergency nurse at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH). SCAHF’s mission is clear: to create a supportive community for warriors and connect them to life-saving blood donors — a community of hope and action.

Inspired by her younger sister, Tamuno-tokoni Omubo-Pepple, who lives with sickle cell disease, Dabota launched SCAHF. At first, the project was a family and close friends affair. “I saw how possible it was to speak to people willing to help,” Dabota shares, realising the immense impact of timely blood donations. Family members with matching blood types will donate every time she falls into crises and when not possible, Dabota starts reaching out to friends and extended family to help save her sister.

Dabota began speaking to other people, persuading them to become willing donors to people like her sister Tamuno-tokoni, a Law student at the Rivers State University. She reached out to more and more prospective donors, expanding the network. “What we have managed to do as an organisation is to build a donor community,” Dabota explains. Names, locations, contacts, and blood groups of donors are entered in a database. They are often contacted when there is a need for blood. The idea of connecting those in need with those who can give is the driving force behind SCAHF

“I am a survivor, but I am part of an organization that supports people like me,” Ada Olisa told us. For people like Ada Olisa being part of the SCAHF community could mean the difference not only between hope and despair but between life and death.

When in crisis, sickle cell warriors need at least one pint of blood from a blood bank. Screened and confirmed blood stored in the state’s blood banks costs between ₦15,000 and ₦40,000 per pint, depending on whether it’s sourced from government-owned or private facilities.

With over 50 registered members, including sickle cell warriors and blood donors, SCARF organises regular blood drives ensuring timely interventions and building a network of reliable blood donors. These efforts are crucial in emergencies, where delays in transfusions can be lethal.

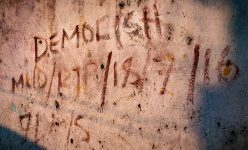

During his son’s final crisis, the first blood transfusion didn’t happen until the next day, Elder Dede recalls, his voice heavy with pain. “We begged and pleaded, but it took forever.” Two days later, the family was forced to purchase a second pint of blood for another ₦15,000. However, the young man reacted poorly to the transfusion, experiencing severe chest pain and weakness. The doctor was called back to intervene but left without administering a replacement transfusion. Hours later Tamuno-Miebaka was announced dead.

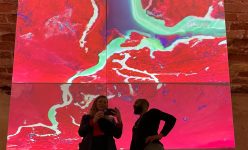

One of SCAHF’s core initiatives is organising regular blood drives to raise awareness about the importance of blood donation. These events not only benefit sickle cell warriors who rely on transfusions during crises but also offer a unique advantage to donors.

One such donor is George Banemi, a passionate volunteer of SCAHF. George first encountered the organization at one of their blood drive events.

At each drive, donors are screened for HIV, Hepatitis B, and other illnesses. Their blood levels are checked, and they receive free health tests that could otherwise be costly. Donors help save lives and in return, gain valuable insights into their own health.

What began as an intention to simply get screened turned into a life-changing experience for George. “I was nervous, I have never donated before, because I didn’t come prepared,” George admits, recalling his first donation.

However, his initial hesitation melted away when he learned how helpful his donation could be. After his first donation, George became a regular donor, scheduling his next donation every three months—the required interval between blood donations. “I feel bad when I can’t donate to another person immediately after my last donation,” George admits. Now, George is a frequent face at SCAHF events, always ready to roll up his sleeves and make a difference.

For George, the beauty of voluntary blood donation far surpasses that of commercial donation. “It’s fine becoming a commercial blood donor,” he says, “but it’s more beautiful when you donate voluntarily because sometimes, the person you are donating for does not have the resources to pay for the things you are asking for.”

Even during the government-imposed lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic, the organisation managed to connect warriors with life-saving transfusions. Since its inception in 2018, the foundation has collected over 420 pints of blood from willing donors and successfully transferred same to SCD warriors.

SCAHF members, like Ada Olisa, a 28-year-old sickle cell warrior, attest to the power of community support. “Now, I know I have people who understand and who will stand by me during crises,” she told us with a soft yet firm tone.

For warriors, being part of SCAHF means more than access to blood—it means being part of a supportive community. SCAHF’s events bring warriors and donors together, creating connections that go beyond medical emergencies.

“Our funding has been mainly family and friends…… we also do welfare package events where people provide services, like space for our events and drugs for warriors,” Dabota tells us. These acts of generosity are what the organization relies on to cover operational costs like providing food and drinks for donors and a few welfare packages for sickle cell warriors.

The fight against sickle cell disease remains an uphill climb for SCAHF. The foundation is often overwhelmed by the sheer number of patients in need and limited by inadequate healthcare infrastructure and funding.

For Elder Dede, the loss of his son will always be a source of pain, “I sometimes get lost, thinking of the death of my son.” The sickle cell crisis is an unimaginable ordeal, affecting both carriers and their loved ones, often leaving them feeling isolated and bitter. It is a relentless struggle against pain, stigma, and a healthcare system that sometimes fails when needed most.

For SCAHF, the mission continues—not just to save lives, but to build a future where no sickle cell warrior feels forgotten.

For more on living with Sickle Cell Disease, read here; and for more SoJo stories, check out here and here. This SoJo Programme was made in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch. This collaboration was made possible by NAMIP.