Power to Improve

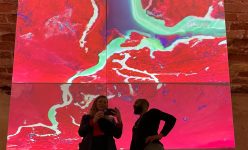

Ibitein Polo is a close-knit neighbourhood in Port Harcourt’s Baptist waterfront area. Like other waterfront communities, it developed organically with minimal government planning or support. Though not officially recognized on Rivers State’s map, it is as old as the city. However, Ibitein Polo faced a critical challenge: its wooden power poles and haphazard wiring posed significant risks to residents and businesses.

In Nigeria, the lifespan of wooden poles depends on several factors, including the type of wood, environmental conditions, and the pole maintenance regime — or lack thereof. While they can endure for decades under optimal circumstances, in Ibitein Polo, the poles had long passed their prime.

Their decay was impossible to ignore as bare conductors, the cables that run between poles and supply power to buildings, frequently fell. During the rainy season, concerns grew. Rotten poles threatened to snap during storms, dropping live wires on zinc roofs. “Whenever it rains with a heavy storm, everybody will be afraid if one of these poles will fall on any building,” Hon. Iyowuna Morrison, the former community secretary, explains.

Under the leadership of Mr. Yikabo Precious, who served as the light committee chairman in 2019 and is now the community chairman, Ibitein Polo decided to act. In so-called informal settlements like Ibitein Polo, leaders often emerge through popular formal appointment process or elections to coordinate community affairs. One such role is the light committee chairman, tasked with addressing power-related issues often neglected by official entities like the Port Harcourt Electricity Distribution Company (PHED).

Pointing to a part of his building with a broken roof, Mr. Precious said, “That broken roof over there was destroyed by a wooden pole that fell off. Imagine a pole with a cable falling onto a roof; no be wahala be that?” Precious recounted how he had begged PHED officials to remove the pole but was met with silence. “I had to contract an electrician who came and did the job,” he added bitterly.

Number 15 of the Consumer Rights section of the Nigeria Electricity Regulatory Commission guidelines states that “it is not the responsibility of electricity customers or communities to buy, replace, or repair electricity transformers, poles, and related equipment.” However, after repeated pleas to PHED went unanswered, the residents of Ibitein Polo took matters into their own hands. “Waiting on PHED meant waiting till infinity. You have no choice but to do it yourself,” Hon. Morrison said.

With limited financial resources, they tapped their funding streams: drawing from their traditionally received “Okoloba Pike”, money paid by residents erecting a new structure. Revenue was also generated from a community borehole scheme, where households connected to this scheme, pay a monthly contribution of a 1,000 Naira to the community. In addition, residents were levied based on the size of their apartments—500 Naira for a single room, and 1,000 Naira for two rooms, with larger spaces contributing more.

Through this effort, the community raised 1.7 million Naira, enough to install 18 new concrete poles. “It was done solely by the community, no help from anywhere,” Hon. Morrison emphasized

The community contracted a local factory in Woji to produce and replace the poles. Due to Ibitein Polo’s dense layout with narrow dirt tracks, the factory agreed to manufacture the poles on-site. Materials such as sand, chippings, rods, and cement were carefully costed and made available. On the agreed day, the factory workers set up production at strategic locations within the neighborhood. “If we can mould in our communities, it will be better due to the road layout,” Mr. Precious recalled. Community youths volunteered to assist, and the workers were lodged in a nearby hotel and provided meals throughout their stay.

Under close monitoring by community engineers, the poles were constructed, left to dry, and later installed by the youths. “Installing those poles was risky. It was a fifty-fifty deal as it could fall off at any time and claim a life,” said Mr. Precious, noting the absence of proper equipment and safety protocols.

Residents who could not offer the needed labour, supported the project by providing food, money, water, and drinks for the volunteers. Every step of the project was documented through videos and written notes. While the community understood that all electrical infrastructure legally belonged to the Power Distribution Company, they knew waiting for PHED would mean indefinite delays. “You cannot wait for them, like 3 years, 4 years, 10 years. You do it to enjoy your life,” Hon. Morrison remarked with resignation.

When the project was completed, PHED officials were invited to inspect, approve, and connect the new poles to the power distribution grid. The officials confirmed the quality of the poles and accredited them for use. “Yes, they saw the quality.” said Mr. Precious, “The solidity of the poles is that strong. NEPA [the acronym for Nigerian Electricity Power Authority, which most Nigerians still use to refer to any institution involved in electricity generation, transmission or distribution] appreciated us,” Mr. Precious said with a smile.

Despite their efforts, the community’s request for a waiver on one- or two-months’ electricity bills as a gesture of appreciation was declined. “Yes, we pay bills,” Hon Morrison remarked. “Even during the period we cast the poles and connected them, we still paid bills. Up till now, we are paying.”

More than a year after Ibitein Polo installed 18 new electricity poles, the community continues to face challenges with damaged bare conductors.

Hoping to resolve the issue and address low voltage in parts of the community, the current Ibitein Polo chairman has reportedly held several meetings with PHED officials to request the provision of the needed bare conductors. Over a year later, the wait continues.

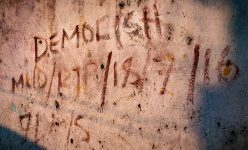

Walking through the community, I noticed that all the concrete poles had “IBITEIN POLO” inscribed on them. “Ibitein” means “the best of them all” in Okrikan. Surprisingly, a wooden pole still stood beside a church building. Hon. Morrison explained that the church had requested the pole after it was removed from another location. When asked about the safety implications of this decision, he simply smiled and said nothing.

Reflecting on their efforts, Mr. Precious shared that neighbouring communities had sought guidance on replicating the project. “Some even went ahead and called us to help erect the poles,” he said. “But I told them it’s self-help and risky.” He encouraged others to mobilize their residents to take similar action.

For Ibitein Polo, the installation of the new poles is a major step toward improving the stability and safety of the community’s power supply.

Though informal and invariably described in the language of marginality, communities like Ibitein Polo represent Nigeria’s core urban condition. Lacking state provided services, they display a remarkable capacity to plan, mobilise and manage. They elect leaders, they levy taxes, they develop infrastructure plans, they engage contractors and execute civic works. Local resourcefulness rushes in to fill the vacuum left by the state government. However, while Ibitein Polo could erect 18 concrete poles, they cannot guarantee the electricity that flows through the wires. Despite their new poles, they often flick the switch, but the lights don’t always turn on.

Want to connect to more stories about power? Check out here and here.

This SoJo Programme was made in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch. This collaboration was made possible by NAMIP. For more, check out here and here and here.