Trash to Cash

In some communities in Port Harcourt, the morning begins with the sound of young men like IK. Casually dressed and carrying sacks as they move through our neighbourhoods, we always hear them before we see them. The clack-clack of the iron rings they knock together and their familiar calls “Iron condemn, condemn fridge, condemn radio, all the condemn, I dey buy”. For Others collecting polyethylene terephthalate (PET) Bottles is a big win.

For them, nothing is truly condemned. As they call out, they also search the parts of the street we overlook, a short rod with a curved hook in one hand, a magnet in another, they sift through gutters and refuse heaps.

As well as hooks and magnets, they also have cash in hand. This they exchange for old and unwanted items whose value they assess on the spot. This provides small extra income for households, less refuse in the gutters, and gainful employment for people like Mr. Jude.

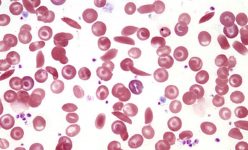

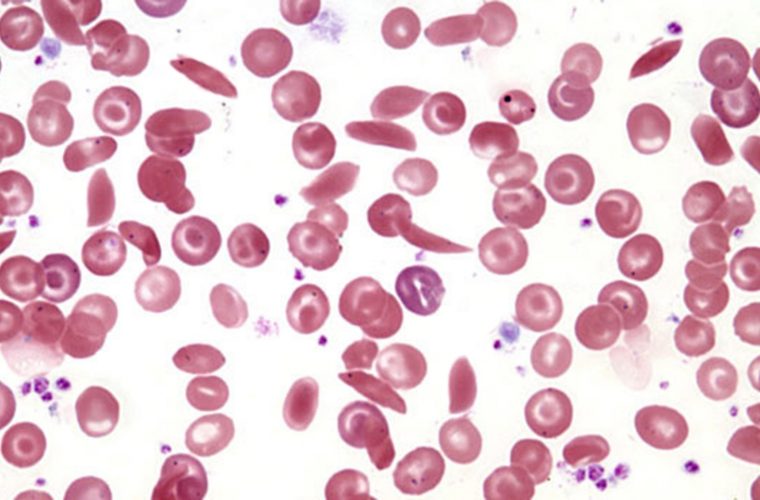

A 2017 World Bank report shows that Nigeria generates about 32 million metric tons of solid waste each year, and that number is expected to increase to 107 million tons by 2050. The National Policy on Solid Waste Management report, released in 2020, claims that less than 20% is collected through a formal system. With a population of over 200 million people, the country ranks ninth in the world for plastic waste production.

In Port Harcourt, the challenge is visible. Piles of plastic, rubber, food scraps, empty tin cans, aluminium, and iron clog our waterways, pollute our environment, and threaten public health.

Our cities are growing much more rapidly than their capacity to manage the waste they produce. And the city’s informal settlements tend to be the hardest hit. Often low-lying, waste from across the city is carried into them by poorly maintained drains and storm runoff. Piles of litter exacerbate flooding and intensify groundwater contamination and other public health threats. The closest official refuse collection site for residents of Okrika waterfront is situated opposite the Port Harcourt Cemetery, up a steep path and at least 15-minute walk to reach. This discourages many residents from using it. Mrs. Ogechi Godknows, admitted, “I go by myself to throw my waste into the river around my community.”

Mr. Douglas is a general waste collector. He takes it all. With over 20 years of experience and five employees whom he pays a minimum of N20,000 monthly. He moves through neighbourhoods like Trans-Amadi, in the Port Harcourt City Local government council area, pushing a cart and calling for attention with a loud honk: “Peee Peeep!” For Mr. Douglas, “This is cool money.”

Douglas gets paid daily or monthly from his already-established clients whose premises he visits daily, or weekly depending on the waste collection arrangement. “One thing that makes me happy doing it is because I don’t go to beg anybody at the end of the day. … This is where I sign my cheque.” As Mr. Douglas approaches a customer’s compound pushing his cart, he calls their attention “Peee, Peee Peeep” honking as loud as he can with his mouth to gain access into their premises.

“As long as people are consuming, there is no way you cannot have waste, every day you will have waste,” Douglas explains. He picks up the trash can and empties it into his cart. Douglas carefully sorts all the waste by hand, piling it into different sacks by category. All paper, nylon, plastic, aluminum, and metals are initially stored together in a huge sack. All glass bottles go in a second sack. “When I didn’t know something like this, a Lebanese man taught me to keep all plastics, he will show me where to sell it”, Mr. Douglas tells us.

Mr. Douglas gets paid on each side of the service. After being paid to cart the waste away, he carefully sorts it. After sorting, the bagged waste is taken to a scrap center, where he is paid again. The remaining material is transported to a dump site.

“This business is my own oil company; I have done it for over 25 years.” “I don’t want to stay somewhere and be idle,” he said, at the end of the day you go out, you come back with something.” So, he decided to make a job for himself.

“Apart from the waste we select, sometimes we dey see important things like shoes, wristwatch, documents, and even money for dustbin” he continues. Some of the shoes and wristwatches nothing happened to them, so I take it and dress with it, I no thief am.” He emphasized.

Collected wastes are taken for scaling. The heavier the waste the more money the collector earns.

Scrap collection sites are scattered across the city. These sites are situated in open spaces and are typically hired by a group of men who often times live in makeshift structures within the premises.

Their centers are always fully packed with already sorted waste, positioned in spaces allotted as though by tribe. Plastic bottles are squashed, tied in large mosquito nets, and stacked on top of one another in huge conglomerations of miscellaneous plastic.

Aluminium and iron have their own allotted storage spaces Meanwhile, cardboard is neatly folded and stashed in a covered space, safe from the rain.

We followed Mr. Douglas to a waste collection site, there, we saw 2 young Hausa-speaking men, rush to weigh his haul and negotiate prices. It weighed 4.5kg, each Kilogram cost N200.

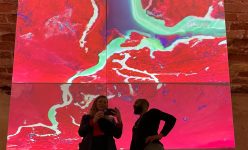

At scaling centers across Port Harcourt, trucks of various sizes roll in, loaded with sorted waste. From here, the waste is transported to recycling facilities like Recyclift Recycling Technology Company, located in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State.

“We buy PET bottles from all these scaling centers,” says Irege, the company’s director.

Recyclift started small, initially collecting waste directly from households. “We used to go around neighborhoods, providing bags for people to separate plastic bottles,” Irege recalls. Over time, the company expanded, shifting from collection to purchasing waste from individuals and informal waste pickers. “Now we’ve grown to buy at ₦500 per kilo from people who bring these bottles to us,” he adds.

Recyclift’s goal is clear—to crush 100 tons of plastic waste weekly and export the processed pellets. Mr. Irege shared with us, “we crush 3 tons of plastics in 4 hours.” With over 50 workers on ground, workers work in shifts of day or night, observing 1 day rest weekly, to achieve the the company’s goal.

At Recyclift’s operational base, workers like Victor play a crucial role in the recycling process. Victor operates the crushing machine. He joined the company 8 months ago, he earns ₦80,000 monthly. “I am a graduate of Mass Communication,” he said. I was a classroom teacher earning 30,000. I work here now, and I’m happy with my job. Aside from my salary, I earn extra every time I work more than the target,” he says. I also sell plastics I gather, back to the company, so, it’s a win-win for me” Victor explains.

Under the hot afternoon sun, women of all ages sit under large umbrellas, their hands moving swiftly as they pluck off plastic covers and rings with practiced precision. The canopies above them, provided by Recyclift, are more than just shade—they are a shield from the scorching sun and the unpredictable downpours that often drench the city.

They chat and laugh as they sort through the bottles removing their covers and rings, the sound of the rhythmic clinking of bottles fills the air.

“We employ the unemployable,” Irege says, pointing to women with pride as they work. “And they’re happy to work and earn a living.” One of these workers, Grace, a middle-aged woman, shares her story. “I no see who go employ me anywhere, plus I no get money to sell market. My neighbour naim tell me about this place.” she explains in Pidgin English as she sorts bottles by color.

After sorting, the plastic bottles are washed and placed into large mosquito nets, which cost ₦2,500 each. Once filled, these nets are weighed and rolled in for processing. The plastics are then crushed, recycled, and transformed into plastic pellets, ready for export—driving the economy forward.

For Ijele, a trained lawyer and CEO of Recyclift, the mission is more than just recycling—it’s about solving the problem of environmental pollution. “We will continue to have plastics with us here in Nigeria,” he says. “Our work helps Port Harcourt cover its carbon footprint,” He continues.

the environmental cost of plastic waste is a growing concern. In a telephone interview, climate expert Julie Greenwalt shed light on the broader impact of plastic production and disposal. “The production of some materials, especially plastics, requires oil and fossil fuels. The more plastics we produce, the more we rely on fossil fuels,” she explained.

Julie emphasized the role of recycling in reducing environmental pollution. “If we can recycle, especially plastics, we reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.” She pointed out that in Nigeria, plastic waste clogs waterways, leading to severe flooding and other environmental hazards.

“If recycling is done successfully, it helps reduce the amount of waste on the streets, prevents blockage of natural water flow, and keeps the environment cleaner,” she added.

Despite its growth, Recyclift faces several challenges that make operations difficult. One major issue is the cost of renting an operational space, “We pay to use this space,” Mr. Irege told us, “and it is not cheap at all,” he adds shaking his head.

“Maintaining the machines is also expensive.” Constant use leads to wear and tear, requiring regular servicing and repairs. Transporting materials from neighboring states is also costly, sometimes reaching ₦350,000 per trip.

Our generator is a 150KVA and we use a minimum of 50 liters of diesel, which cost at least 50,000 daily.” Recyclift CEO Barr Ijele explains to us. Frequent outages force the company to rely on diesel-powered generators—a costly necessity to keep the machines running. “as long as waste will constantly be generated, we will keep doing what we do,” Ijele tells us with a resolve.

In the past, waste was often burned, contributing to environmental pollution. But today, recycling is changing the narrative—turning waste into useful products, creating jobs, and reducing harm to the environment. Through initiatives like Recyclift, plastic waste is no longer just trash—it’s an opportunity.

This SoJo Programme was made in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch. This collaboration was made possible by NAMIP. For more, check out here and here and here.