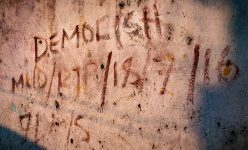

Kpofire: The Burning Economy

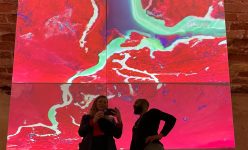

In the early hours of Saturday 17 October, 2020, a fire broke out in Ibimina-polo, an informal settlement close to Creek Road Market, where people from all over the city come to do business.

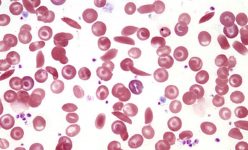

A Hausa ‘job boy’ was pushing a wheelbarrow full of ‘kpofire’, a locally-produced kerosene tapped from the pipelines of some of the richest oil companies in the world. The crude is refined artisanally. Loaded into small canoes, large wooden hulks or even giant oil tankers, this consignment was rolled passed Mrs Esuomene’s shop on a single wheel. Like many people in waterfront communities, Mrs Esuomene, a kpofire seller herself, did not have a kitchen in her shop. She cooked breakfast on a makeshift stove in front of her kpofire store. Like ‘pure water’, this kpofire is transported in plastic sachets. One slipped out of the job boy’s wheelbarrow, leaking and splashing onto Mrs Esuomene’s cooking stand. It exploded, setting her shop and others around it, ablaze.

Mrs Esuomene, along with her adult daughter, Evelyn, was inside the shop at the time of the explosion. They were both taken to the hospital with severe burns. But the mother died. Evelyn survived, but with scars on her face, hands and along the right side of her body, and terror burnt into her.

Some of the community fire fighters, including the community chairman, also sustained minor injuries while trying to extinguish the fire. Millions of naira’s worth of neighbouring property was burnt down. Madam Lucky, whose shop is behind where the fire broke out, said that, upon seeing the thick smoke, she was “in a serious shock.”

“I never expected this to have happened,” she cried.

Over N250,000 worth of Madam Lucky’s goods were destroyed. That number doesn’t include the 300 bags of ‘pure water’ she lost to the fire extinguishing effort, sachets that were passed from hand to hand along the human chain running from Madam Lucky’s rapidly-depleting store to where Mrs Esuomene’s stove used to be.

Johnson Victor, a local resident and businessman who helped to put out the fire — and was burned himself in doing so — recalled how severe it was. He said that many people from different corners of the community, as well as from neighbouring communities, came to the rescue.

The people of Ibimina-polo say that the kpofire business sustains their community. And while some understand the dangers of the industry, others feel that the amount of money made by the trade outweighs the risks.

“To be honest, it’s not good for kpofire business to be around living communities because it’s dangerous, explosive and it costs people’s lives,” said Patrick Sunday, a mechanical engineer whose office is in one of the communities where the kpofire business operates.

However, he conceded that the trade is good for the host community’s economy.

“The kpofire business is what people from this southern part of the country are sustained with, despite its dangers,” he explained.

Mrs Oprite Sokari, a housewife who lives in one of the neighbouring communities, said, “The youths feel they are making urgent money, forgetting the fact that they are endangering their lives and future, because of the lack of jobs. The kpofire industry is not good for communities where people live because it has caused so many incidents, just like the one that recently happened, which costed lives.”

She recounted a similar incident, when a neighbour was operating a kpofire business out of one of the apartments in her compound. There was an accident and the building set on fire, leaving some residents dead.

Mrs Sokari was pregnant at the time. What she saw and felt that day convinced her that kpofire is not worth the lives it puts at risk.

Samuel Anga is the CDC chairman of Sekinama community, a larger community which comprises five smaller ‘polo’ communities, of which Ibimina-polo is one. He remembers weighing up the pros and cons of the kpofire business with other community leaders.

“The polo chairmen, from time to time, we used to discuss on how to curb this kpofire activities in their various communities. But unfortunately, it has become part of life. A syndicate, they are a form of cartel. If you try to stop them, it’s as if you are trying to stop them from their means of livelihood. They can even plan and eliminate you.”

The CDC chairman posits that the government should provide a safe area in the community for the kpofire boys to do their work. In the case of his community, he suggests, the community jetty.

“An open place, in case of any fire, it will be very easy to quench. Even the fire service can drive in there. But inside the community, it will be very difficult. Even if fire service comes […], they might not have access to get to that point that is burning.”

Although he notes the dangers of both the kpofire trade and its tradesmen, he concedes that the kpofire industry is good for the community.

“I like them, because the government is not doing enough. […] We are all dependent on this kpofire for our kerosene. Look at cost of gas. Now I heard that it’s about 8,500 or so. Just a medium cylinder. So the economy is biting hard. […] This is the only way people survive.”

Mrs Esuomene, however, did not survive.