More Power

For the first time, at 83 years old, Elder Mike Opute turned on the light without the accompanying noise and fumes of a generator. He does not know how this small miracle is connected to a kidnapping that took place six years earlier in a community in a neighbouring state.

“I have experienced light before I die in this community, and that is why I came this morning to say thank you,” Elder Opute said to Dr. Fyneface Dunamene Fyneface, the Executive director of Youth and Environmental Advocacy Centre (YEAC).

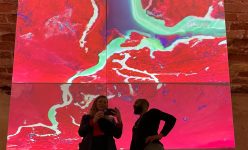

Five months earlier, Dr Fyneface’s NGO had commissioned NXT Grid to install a 90KW solar-powered mini-grid in Umuolu, a fishing settlement in the mangroves of Ndokwa East Local Council, Delta State.

Umuolu had never been connected to the national grid. There wasn’t a single electricity pole in the community. If a light came on, a generator would have to be powered up first. This meant that the privilege of light was costly, noisy, and polluting.

“Records available to us [show] this community has been in existence for 700 years, and we have not seen light,” Kingsley Ogaranya an indigene of Umuolu community and a site technician told us in a telephone interview.

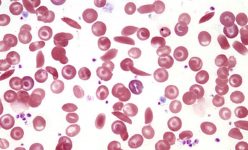

A 2024 survey by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in collaboration with the World Bank reveals that only 53.6% of Nigerian households have access to electricity. While 82.2 percent of urban households have some access to power, no matter how unreliable, only 40.4 percent of rural households are connected to the national grid.

Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil producer and the second-largest gas producer on the continent. However, at conservative estimates, between 10% and 20% of daily production is stolen and ‘bunkered’—either refined in local ‘creek refineries’ or sold illegally on the international market. The Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL) and the Ministry of Petroleum estimate that the country loses between 200,000 and 400,000 barrels of crude oil daily due to theft.

NNPCL’s Group Chief Executive Officer, Mele Kyari, revealed that since 2022, 8,684 illegal “boiling point” sites have been deactivated, and 5,913 of 6,610 illegal pipeline connections have been removed. However, over 1,000 remain, with new ones reappearing daily, hindering the fight against oil theft.

YEAC Nigeria, and its executive director Dr. Fyneface, have long been advocating for the regularising of these creek refineries through the establishment of the “Presidential Artisanal Crude Oil Refining Development Initiative” (PACORDI), which he developed on July 27, 2020, and presented to the government of Nigeria to modernize, standardize, and legalize artisanal refineries into the national economy. They argue that this would help shift a violent, dangerous, and deeply polluting economy from a base of illegal oil bunkering towards one of regulated ‘artisanal refineries’. Yet this shift would still leave local energy economies rooted in unsustainable fossil fuels.

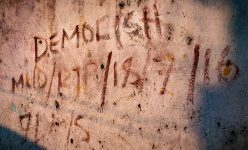

On 25 November, 2019, Dr Fynface was abducted. He had been in an Ogoni community on an advocacy mission focused on the environmental impacts of bunkering. His work to expose the devastating ecological implications of this practice, and his demands for environmental justice, had made him a target. Held bound by his abductors, he listened as they revealed their own struggles. “They told me they do illegal refining… security is not allowing them to do their business,” Dr. Fyneface recalls. Their economic survival depended on crude oil theft and makeshift refineries—a dangerous, polluting trade born of systemic neglect. They saw no other options for themselves or their communities – oil producing communities that didn’t even have electricity. Were there no other ways to bring power to these people, Dr. Fyneface wondered. Negotiating the installation of solar lights within their community became part of the deal through which he regained fhis reedom. “I went home, developed the idea to help climate change and create small and medium-scale enterprises that will develop [the] local economy,” he added.

That encounter inspired YEAC to expand its mission beyond advocacy to renewable energy initiatives, merging environmental justice and practical solutions for local economies. This led to collaborations that saw the establishment of YEAC-UK to take on the the responsibility of fundraising for the project, partnerships, including with NXT Grid the contracting firm, and the establishment of YEAC Community Energy and Development, a subsidiary of YEAC-Nigeria, managing resources from paid electricity services.

The solar mini-grid initiative, which started in Rivers State, was designed and installed in Umuolu, the first benefiting community in the selective electrification of rural communities in the Niger Delta region, lighting up the community.

The initiative began in 2022, with the approval of the National Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) “NERC gave the specifications that we must follow to carry out the project,” Dr, Fyneface confirmed.

The plan to start with the Ogoni community in Rivers State did not pan out due to further threats and an unfriendly environment in the community where the idea was conceived. “I withdrew after being attacked at least 4 times, and the last one with a team of foreign media journalists when we visited the community in Ogoni” Dr Fyneface recalled. The Port Harcourt Electricity Distribution Company (PHEDC) had also denied YEAC the right of operation in a community in Abua-Odual Local Government Area of Rivers state, within their coverage zone. “PHEDC said they have right of way over the area so we cannot come in,” Dr. Fyneface told us. They don’t even have their properties there….. what the community had before was from electricity from gas turbine in 1979 to 1980s,” He retorted.

Umuolu was selected from 30 Delta State communities that applied for the solar project. “We asked, is there the presence of a power distribution company? the population of the community, the businesses in the community, is it hard to reach the community, are they friendly?” Fyneface explained. Umuolu met all these conditions, making it an ideal candidate for the solar project.

YEAC worked closely with the community, holding meetings to ensure alignment with their needs. The large majority of Umuolu community members accepted the initiative, demonstrating their commitment by donating the land for the project and contributing to its costs. “we are part of the arrangement on how to get this light, ….. first of all, the community donated the place free of charge, to install the mini-grid.” Ogaranya told us.

Each household paid a ₦10,000 connection fee, which covered for cables and the installation of a meter, and agreed to pay ₦700 per unit of daily electricity consumption—less than the ₦1,000 they previously spent on a liter of diesel.

Eve Imonite, a bar owner in Umuolu told us, “I used to buy 25 liters of original fuel for ₦25,000 and that will carry me for only 4 days, I have my gen on from 7pm till 4-5 in the morning every day,” Eve recounts. Her business depends on power. “Without light it will not be possible, people need cold water and drink.” She explains.

During my visit to Dr. Fyneface, on 30th December 2024, I had seen the software from where he monitors in real time the affairs of the grid, from seeing the site live to seeing the cost each subscriber spends on the go as captured by their meter. Eve had already spent #83,000, “She is our best customer,” Dr. Fyneface remarked. Eve told us via telephone interview, that she does not want to be connected to the state grid because of her experience in Lagos: “you pay them whether or not there is light.”

Community member and site supervisor Kingsley Ogaranya put it simply: “Light is life… our community now has life.”

The solar power installation provided residents with sustainable electricity. “200 out of the 262 structures captured by satellite imagery and on-the-field GPS structure mapping have light.” Dr. Fyneface narrates with excitement. These 62 households unconnected to the grid had initially doubted YEAC’s move to bring power to their community. “Now they all want to be part of it,” He said.

The solar mini-grid operates in two modes: during the day, all electronic devices are allowed, while in the evening, only essentials like bulbs, fans, phone chargers, TV sets, and radios are permitted. Non-compliance leads to automatic power cuts to the offending building.

YEAC’s approach ensures the long-term sustainability of the project. Training local technicians was a key part of the project’s plan. NXT Grid, a renewable power company that develops and operates distributed solar energy, was contracted not only to install the system but also to train local technicians to manage the day-to-day running of the project. This training ensured that the community could maintain and sustain the solar infrastructure long after the installation was completed. One of these technicians, Tabowie Sunday, now oversees the system’s operations. “I was trained to install meters, and resolve minor issues,” Mr, Sunday shared with us. “I will contact YEAC through Fyneface for major problems. On 24th December, a total shutdown occurred due to a burnt fuse.” Sunday told us he identified the issue and reached out to YEAC, who promptly brought back engineers from Next Grid to fix the problem. “As we speak, light has been restored to the community,” Mr. Sunday confirmed. He is employed and paid monthly by YEAC, reflecting the organization’s commitment to providing direct employment to residents. “We employed and pay 3 community members every month,” Dr. Fyneface reiterates.

Despite its successes, the project faces challenges. Rising costs have delayed the connection of the left-out 62 households to the grid. “One meter of cable used to be ₦1,500; now it’s ₦3,500,” Dr. Fyneface explained. Additional funds are needed to cover the connection fees for these households, but the enthusiasm in the community remains strong.

For YEAC, Umuolu is just the beginning. “We want to light up 10 communities in the Niger Delta, one community at a time,” Dr. Fyneface said. With additional funding and partnerships, the organization plans to replicate this success across the region.

The story of Umuolu’s solar mini-grid is not unconnected to the environmental and social harm caused by Nigeria’s oil economy. For years, the Niger Delta has suffered from oil spills, polluted air and water, and the neglect of its communities. Many locals turn to illegal refining to survive, which damages the environment and fuels conflict. The dependence on fossil fuels traps communities in cycles of poverty, corruption, and environmental degradation, as oil theft and bunkering escalate violence among rival groups and trigger harsh crackdowns by security forces. This vicious cycle has left places like Umuolu in perpetual neglect, denied access to basic services like electricity, despite being in the heart of an oil-producing region. The arrival of solar power here is more than just electricity—it’s a break from this destructive legacy, showing how clean energy can heal the deep scars left by the oil economy.

This SoJo Programme was made in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch. This collaboration was made possible by NAMIP. For more, check out here and here and here.