Mapping Migrating Markets

As a community mapping team, we have spent the last few years gathering and sharing information about our neighbourhoods. We have walked our streets with a pencil and canvas map, paddled up drainage canals in a canoe with a GoPro taped to the prow and flown a drone a hundred meters above our rooftops. We have collected data using household surveys, focus groups, transect walks, and a range of other tools to tell the story of the communities we live in. When we went into lockdown at the end of March and were stuck close to home, we decided to put all of those skills to work to understand the impacts of the pandemic on our city through our combined networks, even while mostly indoors.

The shutdown of the city made the vital significance of markets painfully clear. Markets in Port Harcourt are a daily and essential aspect of nutritional, economic and social life in many ‘informal’ settlements and across the city. So, as rapidly as established markets have been closed by authorities, informal ones have emerged to meet immediate local needs. Through the pandemic there has been an evident and urgent tension between market as place of essential exchange and market as place of viral transmission.

We began to research, document and analyse what was happening to our markets through this period. We gained insights into the impacts of the pandemic and the responses of governments, security agencies, traders and entrepreneurs, and ordinary citizens. Markets shape and are reshaping our city. Negotiating the imperatives of health and livelihood around markets in the middle of an infectious disease outbreak is profoundly difficult, but the state’s response to public markets has revealed an often violent disconnect between policy and the everyday realities of the urban majority. The way that sellers and buyers respond to the way duty bearers treat markets reveals much of their resourcefulness, resilience, intelligence and, in some cases, desperation or ignorance.

We’ve pulled out some findings from our local market research here:

The city’s distributed market-making capacity is greater than the state’s centralised market-closing capacity

Although the governor and state planning authorities often speak of public markets as if they were a mere disruption of the city’s orderly functioning, in fact both rich and poor depend on the daily flow of goods through the city’s many markets. Our research has clearly evidenced that a complete shutdown of markets throughout the city is not feasible. It is not merely an act of defiance to continue trading, but a critical function for keeping the population fed, many of which don’t have the facilities or the funds to stock up on goods.

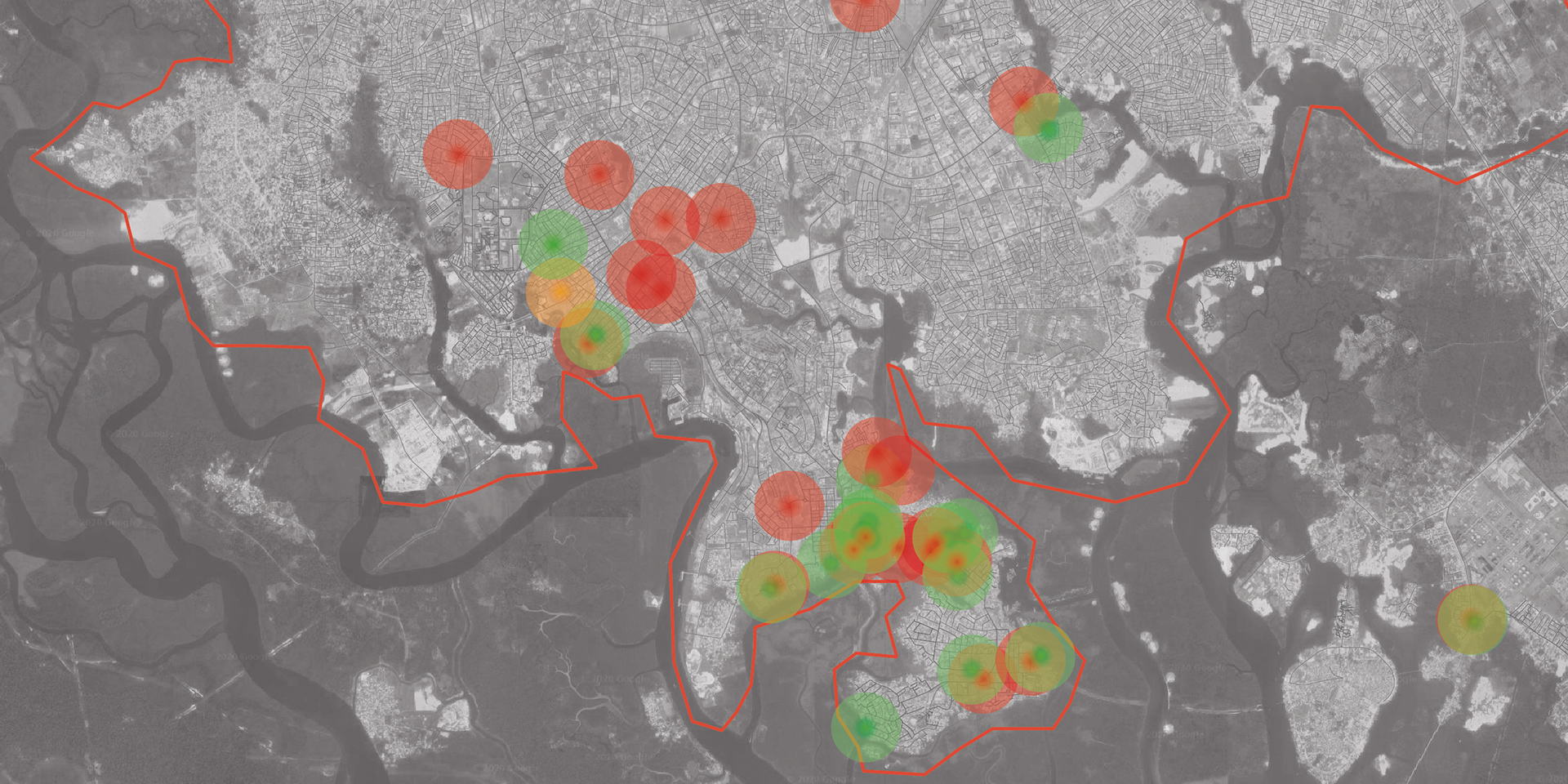

While we certainly have not documented every market that was shut down during the government enforced statewide lockdown, we were able to put 24 different markets throughout the city on the map. And furthermore, we captured 17 new markets that popped up in their stead, as well as one established market that managed to continue functioning despite the restrictions. These ‘New Lockdown Markets’ as we have started to call them, have taken different forms: from small neighborhood gatherings of a few traders, to huge bustling makeshift markets with hundreds of traders, hawkers, porters and fast food sellers.

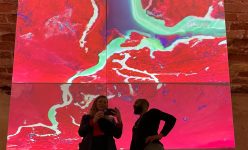

Previously marginalised waterfront communities became vibrant and valued spaces for commerce

Of the 17 new lockdown markets we documented, we found that over half were in ‘informal’ waterfront communities, while many others were located near or adjacent to waterfront communities in the Diobu or Old Town axis of the city. Some waterfront communities simply expanded their small community markets to incorporate more traders, while others opened brand new spaces for selling goods along their narrow community paths and open areas. Mixing residential and commercial activities became a major advantage for residents of these waterfront communities during the lockdown.

Even more surprising was that without the larger markets, like Mile 1 Market or Creek Road Market, some of these makeshift waterfront markets became bustling areas of commerce, not only for waterfront residents, but for people from all over the city. Perceptions of socially and spatially marginalised neighbourhoods, largely operating through their own community governance structures and with limited motor vehicle access, have changed. Widely viewed as sites of crime, they are now also appreciated as sites of commerce. Their informality usually understood as posing the threat of disorder, it is now also regarded as an attractive adaptability. With some informal communities older than the city itself, the informal is often in fact characterised by well-established and deeply layered formalities.

When the roads closed, movement took to the water

When early movement controls were put in place, we noticed that goods entered these new markets through a range of modes, from boats to trucks, carts, public transport, and on traders’ heads. But as the severity of the lockdown increased, and restrictions on movement deemed nonessential were placed not only on market areas but citywide, there was a complete shift to goods being brought into the city by water and then on trader heads or hands to their new selling points. Even for markets further upland, the flow of goods initially arrived at the city by boat before being transported elsewhere by traders.

Waterfront communities with existing jetties or spaces for boats to land became places for trade. Markets typically develop around key transport nodes. As waterways became the main trade routes, markets moved towards the water.

Sometimes the formal just becomes informal one street along

When we started to place all of the new markets on the same map as shutdown markets, we found a surprising trend: some of the new markets have opened up very close to their formal, closed counterpart, sometimes even just across the street or around the corner. As the formal multi-story concrete markets shut down, the streets became vibrant vectors of trade. The distinction of formal and informal is often more apparent than real. For example, the business models of the largest telecommunication companies on the continent have a pillar grounded in the activities of tens of thousands of informal street hawkers selling call credit recharge cards without any employment contracts, benefits or security.

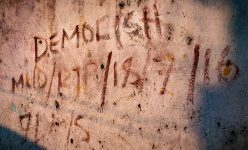

Selling your goods on a sack makes for a quicker getaway

We are used to seeing market traders with permanent or semi-permanent stalls, tables or stands to display their goods. But in all of our research we found that the new dominant spatial form of markets was the sack, with goods on the ground on top of them. Faced with the pervasive threat of having their goods confiscated, or even more violent burning or destruction of market stands, most traders have prepared themselves for a quick escape. Other traders have themselves become more mobile, seeking out buyers by weaving through the streets with their goods on their head or in a wheelbarrow.

Given the uncertainty of their ‘lockdown’ markets continuing from one day to the next, traders look for a spot on the street to place their goods that they can pack up quickly or adjust to different trading hours easily. Since many of these informal new markets are trying to stay hidden, they are squeezed into narrow streets or small open spaces, usually very close to other traders. Counter to the goal of the market lockdown to reduce spread of Covid-19, the response has been the establishment of even more crammed and bustling markets with no semblance of social distancing possible.

The daily order is suspended at night

To avoid harassment by the task force, some of these pop-up markets became night markets, streets that were empty during the day became bustling with traders and buyers under the roar of generators and torch lights. Other markets shifted to very early morning hours, from 3 am to 5 am, so that they could get their daily goods out before the task force started their morning patrols. We documented 5 new markets operating at the dead of night, and another 6 that established early morning hours. Most of these night markets pop-up on major streets and junctions in the Old Town and Diobu axis of the city, in what would be highly visible and accessible spaces during the day.

Money and connections can unlock a lockdown

We were surprised to find that some informal markets kept their normal hours and seemed to avoid much of the harassment from the task force charged with enforcing the lockdown. When we investigated below the surface, we found that many of these markets that avoided, or only had minimal issues with security forces, had worked out agreements with some of the security agents to continue trading. Some of the market unions or market chairmen had pre-existing relationships that allowed for continued operation, or otherwise quickly mobilised to set up levies with traders to pay off task force agents.

Reflecting on these observations, what recommendations might we be able to offer to devise better COVID-19-related market policy and practice?

Do No Harm

Devising policy in the dark, with little data, policymakers might not always be clear how best to proceed. But they should be clear how not to proceed. There is no point in proposing policies that cannot be complied with by the majority of a population. Adopting a punitive approach, even resorting to violence, when populations who can’t comply don’t comply is clearly counterproductive and erodes the trust necessary for any policy measures to succeed. In the first instance, strive to do no harm.

If You Don’t Know, Ask Those Who Do

If one is operating with little data and in an environment where trust is low, seek trusted sources to gather data. Our community mapping team, for instance, have generated deeper and more detailed datasets about some ostensibly informal waterfront communities than anyone holds on any part of the city. Trusted sources are not only able to gather accurate data, but are often better placed to determine what is appropriate data.

Find Space in the Night

The state government attempted citywide market closure and then compromised, allowing certain markets to open for reduced periods. The result, predictably, has been that activity and proximity at market sites increase significantly during the narrowed opening windows. An effective and simple policy response would be to do the exact opposite. Instead of limiting market opening times, allow them to stay open, 24 hours and better regulate them. Extending market access through time would, of course, have the effect of decreasing spatial intensity, as traders and customers space out through the day and night. We know that night shopping is feasible because we have documented the rise of informal, unregulated, night markets as a local response to the closure of established markets. These spontaneous responses, however, have lacked the regulation and encouragement of safer practices that sanctioned markets might feature. Night markets would also likely decrease crime by increasing ‘eyes on the street’ in communities through the night.

To Stay at Home Bring Essentials Close to Home

Furthermore, while night markets allow activity to space out through time, the spatial adaptability of waterfront markets could mean more markets and smaller markets across the city, decreasing journeys on crowded public transport and making it easier for more people to comply with citywide movement restrictions, keeping essentials close to home.

Learning From the Formal Adaptability of Informality

Broadening the scope of analysis beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the spatial trends observed, including shifting of markets to informal waterfront settlements and more disaggregated commercial spaces, provide an interesting case study on urban form and resilience.

The extreme adaptability and mixed-use nature of domestic and public spaces in these communities means that markets have been able to flourish in areas that on the face of it seem to be primarily residential. Spaces where the street and stoop merge to support domestic economies and public commerce are now being recognised as vibrant and attractive places. This trend challenges the citywide single-use development patterns local state planners push. It reveals the more various and responsive character of these communities, which tend to already provide a mix of residential, entertainment, administrative and commercial uses, as more resilient. Despite the profound public health and safety impacts, this pandemic provides an opportunity to rethink what works and doesn’t work in our city. Mapping the movements and mutations of our markets through this time of upheaval offers us much to learn from.

Many people spoke of the violence security forces used in their attempts to enforce market shutdowns. Extortion was common, with traders often forced to pay bribes to have their confiscated goods returned.