Sex Work, Pandemic and Police

“You know who I be? Do you know you are talking to a SARS man?” the officer snarled, leaning towards Pamela*, a 20-something-year-old sex worker in one of Port Harcourt’s informal settlements.

The rifle he cradled in his arms was all the more menacing for his assertion that he belonged to Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad, the police faction feared across the country for their ruthlessness and impunity.

While walking down the street in August 2020, Pamela had been stopped by a truck-full of SARS officers. They told her to get in their van. Then, they asked her how much she cost.

“Oga, because of this situation [increasing economic hardship in the city] na, Nigeria don spoil. So, oya, give me 1,000 Naira,” she reasoned, hoping that cutting her usual price of N2,000 in half would appease the men with the guns.

One police officer, insulted that she would dare to ask for the equivalent of $4 in exchange for her body, began to bargain with her. N500, he offered. Pamela refused. The police officer moved in closer and informed her that he was going to go and get his “boys”. They would shoot her. Kill her.

Pamela accepted the N500 bill, crumpled and brown from countless exchanges between street hawkers’ bras, taxi drivers’ glove boxes, university students’ wallets and corrupt police hands.

Even before the curfews and lockdowns brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, this was not an uncommon scene for the sex workers of Port Harcourt. The city has passed through a series of oil-fuelled, violent crises over the past two decades. In August 2007, the city was also locked down after then-president Yar’Adua declared a curfew. Police and military checkpoints dotted the city. If policing had been marked by endemic corruption before this militarisation of security, levels of brutality escalated after it. They remain high.

Before the pandemic hit, Joy*, who first came to Port Harcourt from Osun state, remembers being at home in one of the city’s brothels, relaxing before a long night hustling on the streets. A police crew broke down the brothel doors, bursting into bedrooms and pulling women out. 13 sex workers in total were arrested that day and taken to a nearby police station. They were shouted at and humiliated until they were given a way out — by paying N10,000, each. That’s N10,000 more than is legal in Nigeria, where police bail is free.

The brothel owner eventually arrived and agreed to go halves with the women on their ‘bail’. In one afternoon, that police station had become N130,000 ($345) richer — almost double a junior police officer’s monthly salary, before bribes.

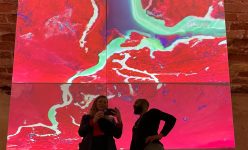

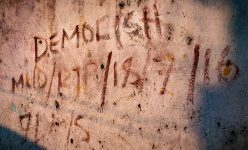

With the arrival of COVID-19, sex workers’ lives became harder still. Places where people congregate in large numbers, including the hotels and bars where the women usually work, were shut down by the government. Police regularly patrolled the streets, even more empowered to arrest any women out in public and to ensure that the hotels where the women live are, in fact, on total lockdown. Hotels in particular were targeted at the start of the pandemic in Rivers State. Governor Nyesom Ezenwo Wike, keen to present himself as getting ahead of the virus, personally oversaw the summary demolition of two hotels which he claimed were still operational, as well as the arrest of the hotel managers.

Victoria Street in Old Port Harcourt Town nestled between St Mary’s Catholic Church and Port Harcourt Maximum Security prison, is one of the busiest streets in the city and hosts a popular red light district. The street has three brothels. Two are ‘hotels’, essentially apartment buildings, where all the tenants are sex workers. The women pay N2,000 a day to work and live inside the building. The other is a ‘lodge’, which hosts a beer parlour and charges sex workers’ clients for the time that they are there. On the surface, the deeply conservative Christian south of Nigeria frowns upon prostitution. But these brothels are staples of the community.

Pamela lives with Ibinabo* and Damilola* in one of the hotels on Victoria Street. The women, confined to the indoors, sit together and look out at their once bustling city through the security bars of their windows, discussing plans, strategies, how they’re going to pay their rent.

“We dey discuss de matter o because e dey worry us,” says Damilola. “Even our rent. For us to pay our rent sef e dey worry us. So we dey discuss to each other say ‘how we go do na?’ Weda we travel go home, and if we wan travel go home, no road. Weda we wan stay, still hunger dey. See everywhere they don block everywhere. No market. No shop. The ting dey worry us.”

“This sickness of coronavirus, e don comot us. For us to get small cash, na work,” agrees Ibinabo.

The women explain that their “sensible” customers, the “big men”, don’t spend the night anymore. The pandemic has given them more than a few reasons to stay home. Now, only a few of the women’s “small small men” come, paying for quickies with their small small N1,000 before rushing back home. The sex workers, relieved for any business during this time, accept the lower offers from their faithful customers and find creative ways to sneak them into the building.

Other businesses in the neighbourhood which depend on the local sex industry have been affected, too.

Victoria Street is usually abuzz from the evening till the early hours of the morning. Men gather around roadside stalls, tearing into sachets of cheap whisky before they head into the brothels. Or, they stop at the local chemists to stock up on sex-enhancing drugs and condoms. When they come back out of the brothels, Hausa vendors sell them fried Indomie noodles, bread and tea to replenish their energy.

Madam Perpetua is a ‘hot drinks’ seller on Victoria Street, offering cigarettes and alcohol to, primarily, the local sex workers and their customers.

“The business no longer flows the way it’s supposed to be,” she complains.

She estimates that her income has dropped by 50%. But she doesn’t blame the coronavirus — she blames the police.

“They are the ones that come around unceremoniously to chase [the sex workers] away,” she says. “Even in the mornings. They do it without any information. They come any time to pick them up.”

One of the brothel owners, a jolly old man named Papa Osai Onoha, agrees.

“Before, police dey pass slowly,” he explains. But now they stop where they see groups of people, emboldened by Governor Wike’s ruthlessness and violence when it comes to enforcing coronavirus directives.

In Northern Nigeria, sharia law dictates that prostitution is illegal. But in the Christian South, the legal status of sex work is more unclear. While legal experts agree that prostitution is not illegal in Southern states, certain laws criminalise acts that may relate to prostitution, such as sections 223, 224, and 225 of the Nigerian Criminal Code which prohibit “procuring, defilement by threat and administration of drugs on girls and women.” Such codes would seem to address the activities of pimps and clients, however.

Chapter 532 of the Penal Code Act of FCT 1990, which applies solely to the Federal Capital Territory, defines a sex worker as an ‘idle person’ or a ‘vagabond’.

“An ‘Idle person’ shall include a common prostitute behaving in a disorderly or indecent manner in a public place or persistently importuning or soliciting persons for the purpose of prostitution,” it reads.

Police officers use ambiguities and broad definitions such as these to target sex workers, and to extort, assault and arrest them. But regardless of the legality of sex work, police brutality of any kind, though routine, is clearly illegal in Nigeria.

“Gender-based police brutality against sex workers is unlawful and it does not matter what these sex workers do [whether they are operating within the law or outside of it],” says Grace Udofia, a criminal lawyer based in Port Harcourt.

“The law is clear on that. Even when a sex worker commits a crime, there are procedures on how a suspect is to be treated until [their] conviction or acquittal. The law [prohibits] brutality of any magnitude.”

Udofia further emphasised that, outside of Abuja, there is a legal consensus that prostitution is not unlawful.

“In the Southern, Eastern and Western States of Nigeria, prostitution is not a crime and so a prostitute cannot be arrested, punished or tagged a criminal for engaging in prostitution.”

Udofia adds that “In spite of the clear provisions of the law in Southern, Western and Eastern Nigeria, many prostitutes still face the brunt of the law for engaging in an act that is not proscribed by law.”

In May 2019, police raided Caramelo, a popular nightclub in the country’s capital city, Abuja, arresting 34 exotic dancers. Two weeks later, they arrested 70 more women at various clubs across the city. Some of the women were charged with prostitution and received prison time; others said they were coerced into having sex with police officers in exchange for their freedom.

In response to a public backlash about the raids, Abayomi Shogunle, Assistant Commissioner of Police and Head of the Police Public Complaint Unit at the time, asserted that prostitution was illegal and tweeted “P [prostitution] is a sin under the 2 main religions of FCT residents.”

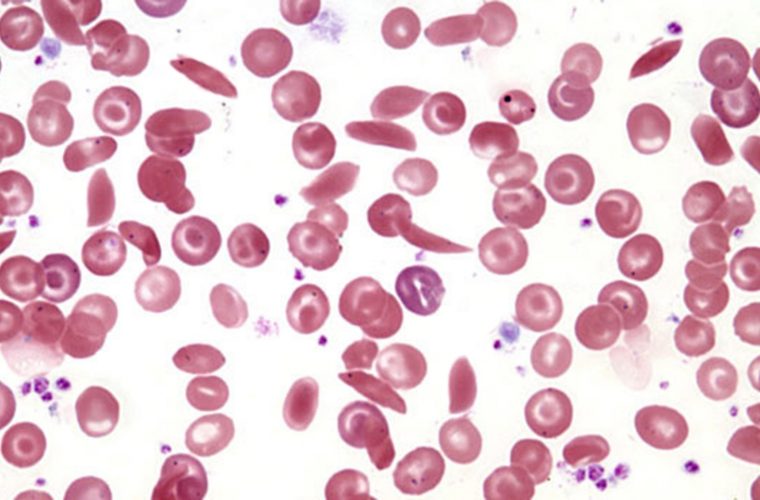

He added, “Medicine says P is spreading HIV & STD, P is lifeline of violent criminals, P don’t pay tax, Nigeria culture frowns at P.”

Gender-based police violence is a systemic issue in Nigeria, and a 2010 Open Society Institute report found that sex workers are the most common victims of sexual violence at the hands of the police.

“Police in Nigeria commit extrajudicial killings, torture, rape, and extortion with relative impunity,” reads the paper. “Nigeria Police Force (NPF) personnel routinely […] commit rape of both sexes, with a particular focus on sex workers; and engage in extortion at nearly every opportunity.”

In fact, field monitors working on this study found that police target well-known red light districts in places like Lagos, Kano and Kaduna. One Lagos police officer said that raping sex workers was common practice, asserting that “this is one of the fringe benefits attached to night patrol.”

“That clearly tells you the mindset of the average law enforcement officer in Nigeria,” says Okechukwu Nwanguma, founder of the Rule of Law & Accountability Advocacy Centre (RULAAC) and contributor to the 2010 Open Society Institute report.

“In Abuja they targeted what they called ‘prostitutes’ and ‘strippers’, and left the men who are the patrons. This shows discrimination in policing crime in Nigeria, which is biased against women.”

Nwanguma’s organisation has been monitoring law enforcement activity during the pandemic, and analysing the effect of the curfews and lockdowns on police behaviour. He claims that the pandemic has exacerbated gender-based police violence, with opportunistic security officers taking advantage of new restrictions.

“A certain COVID-19 taskforce has been arresting people at clubs [in Lagos]. You will see the videos — all of them are women. And so you ask, where are the men? In the case of [the raids in] Abuja, many of the women said they were raped.”

Among international NGOs, calls for sex work to be decriminalised focus on the comparative benefits of safer working conditions, the ability to unionise, government recognition and industry regulation. But in Nigeria, police action on the basis of selective morality, as well as rampant gender-based police violence, means that sex workers are likely to suffer from marginalisation and heavily policed lives regardless of legislation around the issue. The informality of their work and their inability to unionise further puts them and their livelihoods at risk.

Around 65% of Nigeria’s economy is informal, so with places like markets and other public spaces under lockdown, the women’s customers — people like traders, commercial drivers and street hawkers — find themselves unable to make money. They don’t benefit from the safety net of furloughs or stimulus checks afforded to the formally employed in the West who are finding themselves unemployed. Like many in the informal economy in the West, they, too, fall through the cracks.

“My own problem is that make dem open market, open work. So dat dey will fit pay men,” explains Ibinabo. “If men no work, nowhere for us to eat. Dey no go even remember say we dey sef.”

“The lockdown really worry us,” chimes in Damilola.

She recalls having injured her leg at the beginning of the pandemic, back in March, 2020. The city was under lockdown, but exceptions were made for medical emergencies. So she headed to her nearest pharmacy for treatment. A van of SARS officers spotted her. Two men jumped out, one with a knife, another with a gun. She tried to explain that she needed medical attention, but she was met with a slap across the face and a barking order to “shut up”.

“The SARS men told me to sit on the floor and one of them came out from the car with handcuffs straight to me and put it in my hand and dragged me to their car boot,” she recalls.

“All they were saying is ‘Look at this idiot! Small girl like you dey sharp mouth. By the time we deal with you finish you go leave this nonsense business you dey do.’

Damilola’s hands and legs were tied, and she was dragged around the city while the officers arbitrarily arrested more people. Then, she was taken to the Civic Center, also known as Sharks Football Club. The officers removed her handcuffs and untied her legs. Then, they took it in turns to rape her.

“The officers took me turn by turn without a condom through my back and all they were saying was ‘Idiot, you feel you can talk to us anyhow and make noise. Where are you even from sef? See the kind of flesh wey full for your back, ashawo.’”

Five policemen raped her that night. At around 11pm, they ordered her to run away, otherwise they would “take me to their cell and sex me round two.”

Damilola limped back home in the dark, via the pharmacy that she had wanted to go to all along — this time not just for her wounded leg, but also for the morning after pill.

* Not their real names.