Closed Borders, Open Wallets

On 25 March, the same day that Rivers State confirmed its first COVID-19 case, Governor Nyesom Wike ordered all state land, sea and air borders shut the next day, stating that, “Vehicular movements in and out of the state have been banned.” He added, “security agencies have been empowered to strictly enforce this directive. There will be no room for sacred cows because the virus is no respecter of persons.”

On Nigeria’s roads, anywhere that traffic slows down – at a crossroads or at one of the countless giant potholes that punctuate our highways – hawkers appear with goods on their heads: chilled water or soft drinks for thirsty motorists; grilled and peppered snails for hungry riders; handkerchiefs to wipe the journey’s sweat away; pirated music CDs to while away the journey hours. And where traffic is regularly slowed to a crawl, entire markets spring up.

This means that state border posts are busy and buzzing places of commerce. Or they were, before the sudden pandemic-related border closures. Local traders had no time to prepare for the economic shock. This shock has been felt widely and the impacts have increased in severity over the months following the shutdown.

All businesses seemed to have been affected, even the haircare industry. Aniekan told us how her business had suffered.

“I sell human hair, wig and weavon,” she explained. “Due to the closure of border, I can’t make order because nowhere for the goods to pass. Some of my goods have been locked up in my shop, depending on when anybody will come or call me for anyone to buy.”

She went on to say, “Everyone now is thinking of what to eat, so I decided to go back to my cooking business. Let it not look as if without my wig business I won’t be able to feed and make money.”

While most commercial activity has been affected in one way or another, it is the disruption of food production and trade that is felt most widely and most painfully.

Protocols to ensure that interstate food and other essential supplies continued to flow were not mentioned in the border closure announcement.

Much food production in Africa’s most populous nation is carried out by smallholders, and much of the movement of food to market is carried out by a legion of petty traders. This means that at a border, a taxi may be half full of people and half full of bananas; a bus may have its seats crammed with passengers, but lashed to its roof is an oversized bundle of dried fish and yams; a truck may be full of both cows and people. There is often no distinction between goods transport and passenger transport, or between private and public transport.

As minivans and trucks, taxis, tricycles, private cars and motorbikes piled up at mud-bound state borders, directives eventually came through to let food transporters and vehicles with essential goods pass at the border points. Yet how were the police and soldiers to sort transporters of essential goods, who should be allowed to pass, from those passengers who should be turned back? With no clear criteria for exemptions announced, how would such distinctions be made?

In practice, there seems to have been a clear and sole criterion applied by border agents: money.

Though the governor had stated “there will be no room for sacred cows,” border security forces did make room for cash cows.

Mrs Blessing, a fish vendor, told us that before the closure of borders, she paid N1200 to travel from Rivers State to Akwa Ibom where she buys fish for resale. She now had to pay N4000. Nor could she travel according to her own schedule, as she now had to coordinate with commercial drivers to learn when they were ready to travel. Such coordination came at a cost because, in turn, the commercial drivers were collaborating with border agents. All these costs were passed on to consumers, and food prices spiked. As Mr Kingsely had told us, “many of our security formations took advantage of that to exploit stranded citizens, like collecting money to relax the closure at night.”

And so the border shutdowns marked the startup, or rather the intensification, of an economy of extortion.

Mrs Blessing reported paying N500 to pass each police or army checkpoint en-route to Akwa Ibom. Madame Jemima, who trades interstate, told us that the price of goods had tripled, due in part to increased transport costs, but also because, “officers, too, are doing their own by collecting bribe before letting us to pass through the borders.”

It is common to see police and soldiers demanding bribes on highway checkpoints, but the border shutdown order has resulted in this practice becoming not only pervasive but also systematic.

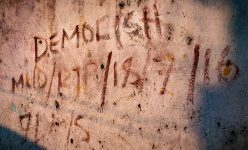

Miss Juliet, who travelled from Warri to Rivers State during the border closure, shared her experience with us. When her vehicle reached the Mbiama-Bayelsa/Rivers border, the border agents, accompanied by a lawyer, insisted that every female in the bus pay N3000, while males were charged N5000 to cross the border. If they did not pay, they were threatened with arrest and enforced quarantine.

Public health enforcement has become a pretext for extortion, in turn compromising public health imperatives. As security personnel asked passengers to open their wallets in order to open the borders, the cost of staples in the city jumped overnight and remains high. With the porous borders officially closed, many found their wallets and their stomachs empty.