Distance Learning at a Social Distance

Mrs Tina’s children all attend prestigious private schools. When the coronavirus pandemic reached Nigeria and the state shut down all learning institutions, her kids’ well-funded schools were quick to send them home with new learning devices, while their tech-savvy teachers transitioned seamlessly to an entirely virtual curriculum.

Mrs Tina embraced the government’s directives, which kept her children in school while keeping them safe from a deadly virus. Her kids, who are between the ages of 7 and 18, started learning through video lessons, while Mrs Tina used the internet to give them extra tutoring and help with their assignments.

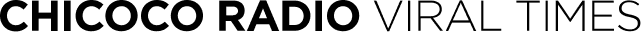

This wasn’t the case for the average child in Nigeria, most of whom live in extreme poverty and study at government schools or under-funded locally-run schools. Teachers at these schools typically haven’t had the exposure to or training for virtual learning platforms. Regardless, without the gadgets necessary for e-learning — or even reliable internet coverage — and without generators — or even money for fuel — most of Nigeria’s children found their education inevitably cut short.

The country’s governing bodies, chronically out of touch with the people who voted for them, didn’t foresee the impact the pandemic would have on these schoolchildren.

Chukwuemeka Nwajiuba, the Minister of State for Education, assured concerned parents that e-learning systems would be introduced across the state. As many schools had been preparing for their promotional and final exams, Nwajiuba promised that teachers would embrace technological innovation to replace face-to-face teaching and limit the disruption of students’ education.

“All parents should please help us,” he said at a Presidential Task Force COVID-19 briefing. “At the point where we are now, we are asking that students can learn online. We have made a lot of provisions for that.”

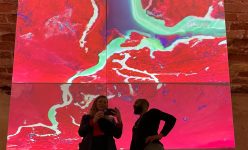

David Philips is the director of a locally-run Sweet Water Academy in Abuja Down, a slum community in Port Harcourt where students’ families don’t have the money for food, let alone iPads.

“The e-learning initiative is a welcome development. But we are limited due to the reliability on local power supply, which is not constant,” he explains.

“[We struggle with] Internet connectivity and the computer teaching skills of teachers. Students aren’t competent at using the Internet, and the computer literacy of most parents in our waterfront communities [is poor.]”

Elvis Okoye, a maths and computer teacher at a community-run girls’ secondary school in Rumueme, agreed that the e-learning initiative was unrealistic for the average Nigerian schoolchild, and that most schools did not promote or facilitate it.

“Despite the government directives to implement the e-learning systems in school, most government schools did not participate in virtual learning because the government did not provide laptops, or phones for both teachers and students,” explained Okoye.

According to UNESCO, approximately 1.5 billion learners globally have been affected as a result of school closures, representing about 60% of the world’s student population.

In Western countries, schools have been quick to adapt, switching to e-learning on digital platforms which were often already used to some extent. In Switzerland, Norway, and Austria, 95% of students already have access to a computer to use for their schoolwork. But in Nigeria, currently the country with the world’s highest levels of extreme poverty, schoolchildren have been especially impacted by a lack of technological connectivity.

“Students in our local communities are left out and unable to access learning due to [the] non-affordability of these technological gadgets,” says Philips.

“Most parents in rural communities barely survive on less than a dollar [a day and are] struggling to feed. They cannot afford to buy laptops and Android phones for their wards.”