Free Ride PT.1

Urban mobility was an urgent issue in Port Harcourt before COVID-19 movement restrictions. But the pandemic has sharply impacted the way we move about our city — particularly for those of us who do not own cars.

With poorly maintained roads — often more hole than tarmac — and dangerous vehicles plying them, with poor traffic management and a culture of reckless driving, Nigeria’s roads have always posed risks. Official statistics record around 40,000 annual fatalities — this is likely a significant under reporting. But for many, it is not so much the threat of death, as the daily struggle of getting to work and moving about with little money and no public transport that is the most pressing concern.

At UTC junction, seven people are crammed into a taxi whose doors are lashed together with coat hangers and whose chassis is a welded composite of vehicles banned from the roads of Europe decades ago. Someone is sitting on the gearstick. The breaks are failing. There are rusty sockets where the headlights should be and there is a turbulent mix of thick white and sooty black smoke swirling behind it, even as it sits idling. The driver forces a gas canister into the already over-full boot and ties it down with a rope to the rear bumper. Beside it, twenty sweating souls squeeze into a fifteen-seater minibus, minus a side door but plus elaborate Premiere League decals and a motto stencilled across its cracked rear window: ‘Shut Up! Are you God?’ Its front wheels splay, eccentrically, and the conductor calls out for one more passenger, impossibly.

With a government-mandated limit on the number of passengers allowed in commercial vehicles, taxi drivers are facing difficult decisions. Should they put themselves and their passengers at risk of contracting and spreading a potentially deadly virus? There is the more keenly felt risk of being stopped by notoriously violent and extortionist traffic taskforces. Should they accept a drastic loss in income? Or should they start hiking their prices by more than double? In many cases, drivers chose the latter option, leaving many people across the city unable to afford their daily commutes.

But June brought a government announcement that promised some respite to transportation challenges exacerbated by the pandemic.

The state government, whose policy posture has always been that free public transport is not feasible, announced the launch of a “Free Bus Scheme to further address the public transportation system and check the community spread of coronavirus.”

We set out to investigate, monitor and report on this new initiative. As mappers who had been locked down since the beginning of the pandemic, we were keen to leave home, safely, and to start work on a new project. As citizens, we were wary — we are painfully familiar with how Rivers State government has historically dealt with new transport initiatives. This certainly wouldn’t be the first time that a high-profile public transit service had been launched, only to disappear just as quickly, leaving behind abandoned infrastructures, vehicles and public trust broken-down.

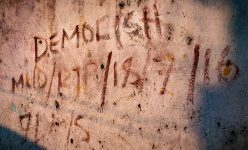

The ‘Port Harcourt Monorail’ — incomplete and abandoned — towers above the cars that rattle along Aba Road. The project was announced by former Governor, Rotimi Amaechi, in 2011, with construction starting in 2012. By 2014, $400 million had been spent, but only 2.3 km of the proposed 19.5 km of elevated track had been built. Around that time, an excited flurry of Photoshopped scenes and promotional videos publicised a shiny, high-tech train on the track, carrying passengers — for the first and last time. The elevated rail remains a visible reminder of the broken promise of a ‘world-class’ public transit system.

There were many failed bus and taxi projects that preceded this. Some will recall the first time a free bus service was introduced in 1999 by then-Governor, Peter Odili. But that free school bus scheme and civil service welfare bus system, once lauded by parents, came with no plan for maintenance, fuel costs, or paying salaries of drivers and conductors. It lasted less than three years.

Then, after a highly publicised transit summit in 2008, Governor Amaechi launched the short-lived Port Harcourt City Bus Service Scheme (PHCBS), through a public-private partnership with Skye Bank. The new bus service, with its ‘luxury buses’, would supposedly fill the gap created by the citywide ban of commercial motorcycles, known as ‘okadas’. The bus service charged passengers N50 per ride, which many found competitive with mini-bus and taxi fares. We even used those buses as part of our ‘People Live Here’ campaign against forced evictions and demolitions, paradoxically being carried out by Governor Amaechi. It remains unclear why this bus system disappeared in under three years. Perhaps it went the way of many projects at the end of a Governor’s tenure, but we may never know since there was no transparency of the agreement terms with Skye Bank.

In another highly publicized move, Judy Amaechi, the then-Governor’s wife, launched her ‘Lady Cabbies’ initiative. Somewhere between 60 to 200 cabs were given out to female cab drivers with a weekly repayment programme. The only legacy of that project are those battered cabs with the faded ‘Lady Cabbies’ logo that have been resold to other — mostly male — drivers out on the road.

Today, the same Governor Amaechi who left behind a legacy of failed transit projects has been serving as the Federal Minister of Transportation since he left office in 2015.

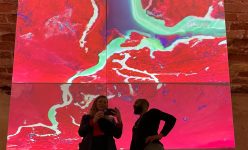

But we couldn’t help but wonder if things would be different this time, especially after our initial scoping trips mapped out the 10 routes that traverse Port Harcourt and Obio Akpor Local Government Areas. We set out to survey passengers and the bus drivers as well as track ridership and stops along the routes. We also interviewed taxi drivers parked near the bus stops about their views on the new service, as well as members of the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW).

Our team of surveyors noted that there was overall high compliance of mask-wearing on the bus. At each stop, a bus conductor met passengers boarding the bus to ensure they had on a mask, gave them hand sanitiser and ensured social distancing protocols on the bus. We observed that few people waited in spaced line at stops, instead rushing out to queue closely for the bus when it came into sight on the road, with no semblance of social distancing.

Since the bus did not have a set schedule, most people would wait around for a bit, but then take a taxi or a ‘drop’ if the bus did not show up. Because of this, many people said that they could not rely on the bus for getting them to work on time. We did observe that some people would exit a taxi if the bus came into view, opting for the free ride and a better chance of being in a socially-distanced vehicle. Many passengers waiting at busy transit hubs like Abali Park remarked that they wished there were more than one bus per route, since seats filled up quickly.

What we found from our survey was that passengers were quite satisfied with the free bus service, and that almost half of those surveyed were using it for their daily commute, despite the lack of a regular schedule. Many of the passengers hoped the service would continue, since it was providing them with significant transportation cost savings. This is particularly important during this period, where most of us who are already living day-to-day have to stretch our resources even further.

Faith Nwogu said that she normally spends up to N600 to visit her family, but was now saving that money. Another passenger highlighted that the bus service had helped him save over N2,000 every week. These savings are significant as almost 60% of passengers surveyed said that the biggest challenge facing their families was reduced work or income. Despite this, many shared our hesitancy to praise the government for the service.

“This is the only benefit I have seen from the government, so I want to continue using it,” remarked Gogo Etete, a passenger riding the bus from Abali Park to Woji.

Unfortunately, our skepticism was warranted. When we came out to continue our survey work on 6 August, barely two months after the free buses started operating, we couldn’t find one. We waited around for two hours with hopeful would-be-passengers, but the bus never showed up — and hasn’t since. There was no public announcement notifying the suspension of the free bus scheme, leaving many people who had planned or depended on the bus that day, and subsequent days, to find alternative means of transport.

We tried to follow up with the Ministry of Transport to uncover what happened but received no official word on where the buses disappeared to or when they would be back on the road. One bus driver said that he thought they were waiting on funds to be released to perform routine maintenance on the buses and that it might be a few days before the service could resume. Those few days turned into weeks, and now months. Another broken promise and another failed project.

Meanwhile, there has been some speculation among Port Harcourt residents on the whereabouts of the buses but still no official statement from the Ministry of Transport. While we don’t know for sure what happened to our buses, we do know they won’t be back on our streets anytime soon.

Stay tuned for our analysis on the data we were able to collect on passenger flows and the bus routes. We have some ideas about how such data, and data collection networks like ours can be used to improve transit planning in Port Harcourt.