Waterfront Vigilantes

Prince Wiro walks through the narrow alleyways of Afikpo waterfront. As he navigates open sewers and buckets of soapy laundry on doorsteps, he talks of his work here a few years ago.

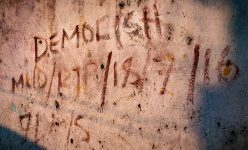

“Afikpo waterfront[…] was ravaged by insecurity in 2019,” pointing to the makeshift homes to his left and his right. “But normalcy has been restored.”

Wiro is a human rights activist and self-proclaimed vigilante who lives in the upland Diobu neighbourhood overlooking its low-lying waterfront neighbour. Afikpo is one of the many communities Wiro has worked in since his organisation, Centre for Basic Rights Protection And Accountability Campaign (CEBARIAC), was officially registered in September, 2020. Since then, the activist has overseen 13 cases, many of which have involved sexual assault on women and girls, some as young as 19 months old.

“It was 2019, March, when the incident happened,” recalls Godstime Lawson, a food seller in Afikpo. She was at home when local gang members broke in.

“Boys was disturbing us. Raping. When they came to your house, they will scatter everything. Took things. Stealing.” The men broke the padlock on her front door and kidnapped her. “I was praying,” recalls Lawson. “I said, God, help me.’”

The gang bumped into another group of local men. Thinking they were policemen, they fled, leaving Lawson in the street.

Lawson’s neighbour, Blessing Amachree, remembers how women in the community imposed a curfew on themselves. “6 o’clock everybody would go to church and sleep […] That’s what was going on.”

People started moving out. “Even my son, my only child that I have, run away from this place, saying he can’t stay this place. […] The incidents, the fights, and the shooting. Stabbing, stealing, raping women…”

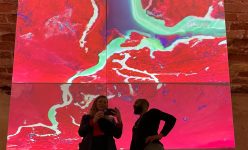

Prince Wiro was contacted by Dennison Amachree, a community leader who was concerned by the surge in violence in his neighbourhood. “We put our heads together and set up this Diobu vigilante [group],’ says Mr Amachree. “Right now, it’s majorly sponsored by Wiro, and we supported him.” Based in the upland neighbourhood where the vigilantes’ leader, ‘Commander’ Prince Tijani, lives, the group patrols the waterfronts nestled in the creeks below. At least 49 such settlements fringe this creek city; over half a million people live in Port Harcourt’s waterfronts.

Mr Amachree says that, since the establishment of the group, crime rates in the community have drastically reduced. ‘Commander’ Tijani, is the owner of a local beer parlour. The team is currently funded by local households, who voluntarily contribute between N300 and N500 a month.

“These guys have been doing great,” says Wiro, sitting in Tijani’s front porch. And they are all guys: although this group regularly confronts issues of gender-based violence in communities which lack safe spaces for women, only a couple of the group’s members are female (one of whom is the leader’s wife). Women are allowed to join the group, but Tijani is typically surrounded by young men in black polos, the words ‘Operation Fearless’ embroidered in red on the back.

“They have tried to reduce crime in Diobu in general, working in synergy with the Nigerian Police and other sister agencies. I believe that if they are adequately funded they will do more better, and crime will be reduced to the barest minimum,” said Wiro of the group he helped establish.

If Wiro’s vigilantes are underfunded, so then are the police, with recruits paid little over N9,000 (around $21) monthly.

The vigilante commander Tijani claims that the police are also understaffed: “The number of police that we have is not enough. Compared to the map land of the state. […] That’s why we are agitating for community policing.”

Although Tijani, and many other Nigerians, use the terms ‘vigilante’ and ‘community police’ interchangeably, researchers use the latter term to refer to official police efforts to work with local communities through outreach initiatives and neighbourhood watch-type programmes.

As he holds a faded self-published magazine filled with photos of suspects he has apprehended, he talks about the crucial role of vigilante groups in reducing local crime. “Right now, as we are here, no policemen here,” he says, gesturing with both hands to the ground below him. The magazine features galleries of beaten and bound ‘suspects’. Some images appear to show corpses. It is unclear how the photographed men were injured or killed, but the magazine suggests that principles of proportionate force or due process are not at the forefront of the group’s concerns.

Nor do such concerns seem at the forefront of official policing imperatives. While the waterfront communities are under-policed, they also face prejudicial policing. Dragnets, in which young men are rounded up and arbitrarily arrested, or violent raids in which police rush in to set fire to illegal local oil refineries, are common.

Lawson experienced this first-hand when she was arrested at her home in the place of a man she didn’t know, whom the police claimed was her boyfriend and had allegedly stolen something. She was held in a cell for two weeks before Wiro was able to bail her out.

While the state police are understaffed, the informal settlements are criminalized. This leads to a vicious cycle of mistrust and friction. The anti-police brutality movement, #EndSARS, which re-emerged at the end of 2020, signalled a new era of challenge to the policing status quo. Dr Aminu Musa Audu conducted research on community policing in the urban informal settlements of Kogi State as part of his PhD at the University of Liverpool. He found that the criminalisation of slum communities created systemic conflict between residents and state security forces, which in turn made community policing less effective. The waterfront communities were ‘structurally subject […] to a culture of vulnerability, stigmatisation, victimisation and scapegoating.’

‘Many communities, because of the breakdown in police, the people have decided to take the law into their own hands,’ says Dr Gbenemene Kpae, Senior Lecturer of Criminology and Security Studies at the University of Port Harcourt. ‘There is a disconnect […] between the people and law enforcement agencies.’

Informal settlements are often characterised as escape routes and access points for criminals. Outsiders are easily lost in their winding, narrow alleys. Without a map in their hands and with scary stories in their heads, police who do enter the waterfronts often do so feeling disoriented and exposed in neighbourhoods they don’t understand. Prejudicial policing has created a deep deficit of trust, and the resulting friction has led to an adversarial relationship between the police and the policed, rather than a collaborative one.

Commander Tijani claims that vigilante groups could help bridge this gap.

‘At times, if police want to go some areas, they call us and we will move with them,’ he says. ‘We know the place better than police. Some policemen come from Kaduna, some come from Zaria, some come from Osun state, different areas. So they will not know here. But we that are from here, we know here better.’

‘[Vigilante groups] are familiar with the history of their people,’ agrees Dr Audu. ‘The Nigeria Police Force personnel are drawn from different parts of the country comprising of different languages and cultural backgrounds so they largely depend on [these groups] to cover security governance gaps, to detect criminals and can help in the fetching of credible intelligence information.’

Dr Lanre Ikuteyijo, Senior Lecturer of Sociology and Anthropology at Obafemi Awolowo University, explains that the cycle can be broken by empowering communities to police themselves and establishing networks seeking to promote social justice. According to him, a ‘bottom-up approach to policing’ can ‘encourage community ownership’ and ‘help […] ascertain the needs and expectations of the community and […] address and solve communities’ concerns.’

However, while an advocate for more decentralized policing, Dr Kpae says that it is difficult to implement in practice, precisely due to the corrupt nature of the police, as well as criminality within the vigilante groups.

‘Sometimes there is connivance between [the vigilantes] and the police,’ he explains. ‘Some of the folks that work in the local vigilante groups are also gang members. There is a downside in the sense that if the […] vigilante happens to be involved in a crime, then the individual from that community [who reports the crime] might end up in problems, especially with the police.’

Moreover, while waterfront residents are generally excluded from official political processes, they are regularly hired as muscle by the government, especially around election time.

‘If the system is not properly regulated and monitored, there are tendencies for arrogation of power and its abuse in the form of extra judicial killings by some of those involved,’ explains Dr Audu. ‘Some of them are mere unregulated instruments in the hands of irresponsible and unpatriotic politicians to perpetrate thuggery and murder, especially before and during elections in the country.’

‘The very first and foremost necessary is legal reformation,’ agrees Dr Lanre Ikuteyijo. ‘Presently, the constitution of the country only recognizes one police which is the NPF. However, just like the governors of the southwestern Nigeria did recently, we could at the national level review that part of the law and make adequate provision for community policing.’

Dr Audu advises that, to address some of these issues, local vigilante groups should be recognised and empowered as a complement to traditional policing, especially within informal settlements.

‘The Nigerian government and other relevant stakeholders should provide appropriate training [for vigilante groups], sufficient logistics, stringent recruitment patterns and advocacy programs in the country,’ advises Dr Audu. ‘Those living in slums also deserve access to decent environments.’

Key to addressing the issue of underserved slums is the creation of safe spaces for women and girls and of paths for victims of gender-based violence to find justice.

‘Agnes’, a teenager from the Orazi neighbourhood of Port Harcourt, doesn’t know much about policing systems or alternatives. But when she was sexually assaulted by the assistant secretary of a local youth organisation two years ago, she knew the local police was unlikely to get her the justice she wanted.

“I love this Mr Prince so much because he tried a lot,” she says, as she sits opposite Wiro at his office in town.

After ‘Agnes” brother told her about Wiro’s organisation, she contacted him, and he ended up escalating the case from the local level to the State Criminal Investigation and Intelligence Department.

‘Agnes’ was relieved. As she clutches the monkey-shaped bag in her lap, she fingers its fluffy face and recalls how Wiro helped her when the local police didn’t seem to be taking action.

“After we reported the matter to him, he went to the [local] police station to find out what was going on there. They were going to drag the case to make it as if [the rapist] was not [guilty]. They were going to side [with] him. [Wiro] saw the way the matter was going on, and then he wrote a letter to the state CID and then moved the matter from that [police station] to the state CID. That was when they took the matter very well.”

“Thank you,” she says, turning directly to Wiro.

“Thank you. You’re welcome,” he replies.

This story began as an independent commission from Agence France-Presse in June 2021. You can find the article from that commission here: https://www.challenges.fr/societe/dans-le-sud-est-du-nigeria-des-citoyens-s-organisent-pour-assurer-leur-securite_777495