The Cost of Social Distance

Social distance does not come cheap.

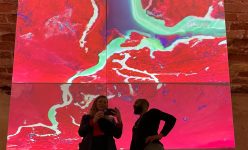

We surveyed 1483 households across three communities prior to the pandemic and for this post reviewed the data through the lens of COVID-19 responses1. Our surveys tell us what we already know from our everyday experience of lockdown in the waterfronts: social distancing is a luxury for those with the space, the services and the resources to be able to afford it. Even if it doesn’t feel like a luxury.

First of all, to achieve distance, one needs space.

In a city, space costs money. A garden would be nice, but a room of one’s own is a necessity.

Across the neighbourhoods our team looked at for these surveys, nearly half of all households live in a single room with two or more people. Some neighbourhoods are significantly denser than the average: in Ibiapu Polo, for instance, 71% of households are single room units. Ibiapu Polo has a population density equivalent to 73,833 p/sq km with mostly single story structures. Compare this with a dense metropolitan area such as high-rise Manhattan Island, with a density of 27,346 p/sq km or 16,000 p/sq km in London’s most crowded borough. In many waterfront communities, a neighbour’s window or door is less than a meter away.

Second, one needs water.

Following seemingly simple advice to wash your hands regularly is impossible if you have no water or it is contaminated. In Ibiapu Polo, only 19% have piped water in their homes. Fetching water at standpipes or public wells means leaving home regularly and gathering with others doing the same.

Third, one needs food.

Without the resources to stock up or store perishables, many households need to work and go to market daily. In the total absence of social security, the alternative to going out to work is going hungry.

If one needs water and food, one needs a toilet.

What does a stay at home order mean when you share a toilet with 500 other people?

If one must go out to work or to find food, social distancing in transit is nearly impossible when people don’t own cars and in the absence of public transport. The paratransit network is critical for waterfront residents – and restrictions on the number of people on a bus or in a taxi makes moving around the city too expensive for an already vulnerable population. Or restrictions are simply ignored.

Because of the pandemic, conditions in communities like ours are increasingly being featured in stories on the national and international news. None of this is news to us.

1This data is drawn from surveys of three waterfront communities Chicoco Maps carried out before the pandemic. They are home to about 7847 people. We mapped 499 households in Amatari polo, 418 households in Darick Polo and 969 in ibiapu Polo. Of these, 79%, or 1483 households, were surveyed in depth. We reviewed all household survey data through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic. While these results might not be representative of all waterfront communities in Port Harcourt, they allow a glimpse into conditions on the ground.

Learn more about the research and advocacy work of Chicoco Maps: drop us a line on the mail in the footer.